Mauro Senatore’s first book in English, Germs of Death: The Problem of Genesis in Jacques Derrida, is a compact and ambitious reading of a significant portion of Jacques Derrida’s philosophical work from his earliest writings on Husserl to unpublished seminars from the 1970s and 1980s. Divided into 5 chapters (2 on Platonism and 3 on Hegelianism), Senatore’s book aims to provide “a systematic elaboration of how Derrida develops the Husserlian concept of genesis through a critical engagement with Plato’s and Hegel’s legacies as well as with the biological thought of his time” (xii). Indeed, if the chapters’ explicit focus are on Derrida’s on-going engagement with Platonic and Hegelian accounts of genesis, life, transmission and inheritance, the book’s toile de fond is no doubt the place of Derrida’s thought in larger debates and developments in contemporary biology and the life sciences more generally. By reading Derrida in light of the transformations that took place in these scientific fields—a shift, broadly speaking, from the genetic paradigm to the post-genetic or epigenetic paradigm—Senatore makes a convincing case that Derrida’s writings constitute nothing less than a significant contribution, “nonphilosophical and nonpreformationist,” to a “post-genetic interrogation of life” (xii). The stakes of this reading are high, since, if Senatore is correct, it would perhaps make Catharine Malabou’s abandonment of the Derridean language of writing premature and unnecessary. What Derrida will have meant by writing and programme, for example, as early as 1967 in De la grammatologie where he already speaks of biological writing and the biological pro-gramme[i], would in fact be quite close to what Malabou will call plasticity in reference to contemporary neuroscience.[ii]

In many ways, the center of gravity around which Senatore’s book turns is the recent wave of interest that Derrida scholars[iii] have taken in Derrida’s unpublished 1975-76 seminar La vie la mort[iv], which in turn makes clear the connection between deconstruction and the life sciences proposed by Senatore, since Derrida devotes a substantial portion of his seminar to discussing the French biologist François Jacob’s book La Logique du vivant[v] as well as the work of Georges Canguilhem. Senatore, with this seminar in mind, reads the Derridean notions of writing, dissemination, trace, etc. as responding to the latent teleological and metaphysical presuppositions that still structured the philosophical musings of biologists such as Jacob. But if Derrida shows how the then recent discoveries in genetics seem only to be a repetition of biological preformationism, this time without a divine creator—and thus of philosophical teleology more generally—, he also attempts to show how the contradictions and aporias in the biological text point necessarily beyond themselves to a new thinking of life, one more in line with the work of the biophysicist Henri Atlan who emphasizes the necessity of living beings not to simply repeat pre-inscribed genetic instructions, but to be submitted to the “aleatory perturbations” of the organism’s environment (xii).

Though a fair amount of attention has been recently given to Derrida’s engagement with mathematics and the formal sciences[vi], Senatore’s book opens up new debates and will certainly path the way for future research trajectories that seek to re-inscribe Derrida’s thought in larger historical and scientific contexts, thus avoiding the typical readings of Derrida that made his work a staple in English and Comparative Literature departments. It is perhaps not even an exaggeration to say that we are in the midst of a paradigm shift—if not at least a renaissance (to which Senatore’s book no doubt belongs)—in critical studies on the work of Jacques Derrida. Beginning with Martin Hägglund’s influential Radical Atheism: Derrida and the Time of Life (Stanford, 2008) and even continuing into the field of intellectual history with Edward Baring’s The Young Derrida and French Philosophy, 1945-1968 (Cambridge, 2011), as commentators have come to insist more and more upon the authentically philosophical nature of Derrida’s project.

Indispensable to this philosophical revival of Derrida is of course the meticulous editing and translation of Derrida’s seminars of which Senatore avails himself. This in turn has given scholars access to Derrida’s teaching as a philosophy instructor where he was often tasked with preparing young students for the competitive agrégation de philosophie. This meant that it was Derrida’s job to prepare students to work through the major philosophical problems of the Western tradition as treated by this tradition’s classical figures. Deconstruction was, it must be said, indebted to these close-readings of canonical texts that are to this day central to French philosophical training. In other words, Derrida is being read more widely as making original contributions to philosophy and no longer merely to literary theory[vii], where deconstruction was seen as one possible grid of literary analysis among others (psychoanalytic criticism, historicism, etc.), or, more generally, as an interpretive method applicable to any field whatsoever (i.e. deconstruction and architecture, deconstruction and legal theory, etc.). Indeed, this new turn in Derrida scholarship is making it quite clear that deconstruction does not consist simply in one possible hermeneutic strategy or analytic framework, nor is it a purely negative or critical project, but rather it uncovers and names in some sense the very movement of Being itself, the quasi-ontological conditions of possibility of all beings, the minimal and necessary structure of meaning and experience as such.

Senatore, rightly, does not shy away from such bold claims and asserts this at the outset: “I argue that Derrida conceives of the inscription-seed as the minimal structure of genesis in general, from biological to cultural genesis. This structure constitutes the element of a geneticism of sense in general—that is, of an analysis that accounts for the genesis of the discourse as well as of the living” (2). But this is not all. Derrida’s originality, according to Senatore’s account, is that this account of genesis in general is strictly “post-genetic,” by which he means that it is a thinking of genesis that is non-teleological and therefore breaks with the model wherein arche and telos coincide, the latter being simply an outgrowth of a potentiality present in the former. If the philosophical tradition from Aristotle to Hegel and beyond—albeit a particular reading of Hegel that has been largely discredited today[viii]—conceived of genesis as essentially the internal playing-out of instructions or a programme present already at the origin (a conception that is mirrored in the biological discourses from preformationism to modern geneticism whereby an organism is nothing other than the result of a set of pre-determined instructions transmitted from one generation to another), a post-genetic theory of genesis that takes seriously the irreducibility of the movement of necessary externalization that defines all beings. Indeed, it is Derrida’s contention that a kind of spontaneous Hegelianism was present throughout Jacob’s book La Logique du vivant. Yet Derrida’s engagement with the life sciences is not simply critical and destructive, but also seeks to to elaborate another thinking of life beyond the opposition life/death. Derrida in turn prepares the ground for the elaboration of a post-genetic thinking of life or what Derrida will come to call “life death”, one that anticipates more recent developments in biological epigenesis.

And yet while reading Senatore’s book, as well as Derrida’s seminar itself[ix], it is unclear how Derrida conceives of the relationship between philosophy and science. At certain moments, one gets the impression that Derrida is suggesting that philosophy, in particular deconstruction, can itself theorize certain objects and structures before the biological and life sciences, that is, that it anticipates discoveries and theoretical developments in various scientific fields. This would appear to make deconstruction a kind of science[x]—or a non-philosophical science? At other moments, it appears that the textual structure that necessarily conditions the life sciences as well as any being whatsoever, renders scientific objectivity both possible and impossible. Deconstruction, insofar as it is attuned to the particularities of the trace structure of beings in general, would be a paradoxical non-science of this most general condition of scientificity as such. Or put differently, and this is Senatore’s claim, it is indeed possible to generalize the notion of dissemination that unconsciously guides the text of biology into a quasi-transcendental structure that accounts for all genesis, “from biological to cultural genesis” (2). And in other moments still, Derrida’s position seems to be close to Althusser’s position in his 1967 lecture course Philosophie et philosophie spontanée des savants, where he explicitly takes up the biological theories of Jacob’s partner, Jacques Monod, in order to argue that there is a salvageable materialist tendency in Monod’s otherwise idealist discourse and that it is the text of philosophy to intervene politically within the scientists to help eliminate unquestioned ideological intrusions that hinder the practice of scientists. But what Althusser takes issue with is precisely Monod’s attempt to generalize his biological findings in order to explain genesis in general. Derrida, for his part, writes in the sixth session of his seminar:

The activity of the scientist, science, the text of genetic science as a whole are determined as products of their object, if you will, products of the life they are studying, textual products of the text they are translating or deciphering or whose procedures of deciphering they are deciphering. And this, which appears as a limit to objectivity, is also—by virtue of the structural law according to which a message can only be translated by the very products of its own translation—the condition of scientificity, in this domain, of the effectuation of science (and of all the sciences).[xi]

Not surprisingly, this session begins with a reference to Gödel, since once we see textuality as a general structure, a paradox of self-reference immediately arises wherein the biological text studied by the life sciences (the genetic code or inscriptions) necessarily refers to other texts, to a text without a non-textual outside. And it is the paradoxical structure of textuality all the way down, so to speak, that seems to legitimate deconstruction’s capacity to outstrip the sciences, if not at the very least, guide their future researches into the textuality that they necessarily study, and which moreover conditions their object of study, but which the science’s fail to thematize. All of this by way of introduction not to delegitimate Derrida’s project, or Senatore’s remarkable interpretation of it, but rather as serious questions and challenges to attempting to think the relationship between philosophy and science from within a transcendental or post-phenomenological framework.

*****

Senatore’s book begins with an introductory chapter that proposes a reading of Derrida’s 1963 essay “Force and Signification”, in particular, a passage where Derrida refers to the Leibnizian scene of divine creation wherein God necessarily brings about the existence of the best possible world. This will then be linked to the more or less contemporaneous translation and commentary that Derrida published on Husserl’s late manuscript The Origin of Geometry. What Derrida develops across both works is a rethinking of genesis that is fundamentally different from what Senatore, following Derrida, calls the logos spermatikos whose biological analog is preformationism, the doctrine according to which an organism develops out of an initial germ which contains already in itself that which it will only later become. Derrida argues, as is now well-known, that meaning or sense cannot be seen as pre-existing the act of inscription, and, in turn, that the moment of inscription should not merely be seen as an external, secondary, and empirical accident, but rather, as an essential condition of possibility for meaning in general. It is in Husserl’s late writings where Derrida finds the basic structure of a rigorously non-theological and non-classical thinking of genesis. Here, meaning must await its inscription, and does not precede the act of writing. Ideality is thus a result of the process that writing names, “only writing permits the full accomplishment of the ideal objectivity of ideality by unbinding the latter from an actual subjectivity in general” (9). And so if ideality is only produced in some sense retrospectively after the event of writing, genesis must be conceived of as a fundamentally creative and productive, and not as an act of revelation of some pre-existing meaning or essence. Since nothing precedes inscription, there is strictly speaking no ideality without writing. This understanding of a generalized writing, as Derrida will later call it, is what Senatore calls “the most general geneticism” whereby writing is conceived as “the structure of genesis in general, from biological to cultural genesis” (14). With Husserl’s account of writing in mind, Senatore turns to the structuralism espoused by Jean Rousset in his reading of Proust, the main subject of Derrida’s “Force and Signification.” It is clear in what way structuralism will necessarily presuppose and repeat the classical scene of Leibnizian creation, which is itself analogous to biological preformationism. The structure of which the work is an expression seems to suggest that literary work is nothing but the fully developed form of what was once a germ latent in the structure itself. In the same way, Leibniz’s God moves from essence to existence, inscribing the former in the latter, and in so doing avoids what Derrida calls the anguish of writing, that is, the necessity of essence being produced not before the act of creation, but only in and by way of the genesis of existence itself. Derrida writes, “the metaphysics implicit in all structuralism, or in every structuralist proposition…always presupposes and appeals to the theological simultaneity of the book, and considers itself deprived of the essential when this simultaneity is not accessible” (19-20). Put differently, the classical notion of genesis makes meaning the result of internal transmission, rather than meaning having to necessarily be constituted as the result of passing through an essential moment of exteriority in the act of writing taken in a general sense, a movement that in turn erases the “externality” of this process of exteriorization.

Senatore then turns to Derrida’s “Plato’s Pharmacy” in the first of two chapters on Platonism in order to differentiate Derrida’s notion of dissemination from the Platonic theory of genesis. Like Leibniz’s scene of divine creation, Platonism “tends to annihilate what Derrida identifies as its anagrammatic structure—namely, the site of the concatenation of forms, of the tropic and syntactical movements, which precede and render possible the concatenation or movement of Platonism itself as well as of philosophy in general” (26). Reading Derrida’s famous essay alongside the recently published seminar on Heidegger from 1964-65 Senatore insists upon the necessity of refusing to “tell stories”, that is, to assimilate being and Beings and to nominate one particular being to be the cause or ontic explanation of the origin of beings. Indeed, the early sessions of Derrida’s lecture course are devoted to investigating what he calls “ontic metaphors” and the necessity to think with them—what is needed most of all is not that we simply abandon these metaphors, as if that were possible, but rather think their necessity and introduce new ones into philosophical discourse. The discussion of metaphoricity brings Senatore to a discussion of the notion of a living logos in Plato’s text. Despite Plato’s attempt to describe the genesis of the logos without recourse to an ontic metaphor, the origin of logos is nevertheless inscribed in the zoological and biological metaphor of generation—Plato is necessarily forced to think speech’s difference from writing as the result of the former’s having a father, that is, its being accompanied or even chaperoned by the direct source of its emission. Whereas writing is orphaned, a dead letter left to circulate without the possibility of response and responsibility, the voice is a living logos that can answer directly and respond to all inquiries addressed to it. Senatore writes, “This suggests once more that the structure of the logos constitutes a metaphor borrowed from a certain understanding of the living and thus that the relation to its father (the noble birth, the body proper, etc.) hinges on a genetic and zoological explanation” (34). But Derrida’s argument is stronger: it is not simply that Plato appeals to the metaphor of paternity and biological generation to explain the origin of the logos in the voice of the speaker, but rather that the casual order of determination is precisely relational. The existence of logos produces the familial relation and not the other way around such that “the concepts of the living and of the zoological process of generation are grounded on the concept of logos and on the relationship between the logos and its subject respectively” (35). Now this conception wherein the logos is the logic of the living is precisely what Derrida seeks to rethink. Indeed, the problem is less that metaphors were imported into the text of philosophy whereas they should be ideally left out of it, but rather that the chosen metaphor makes the production of living logos in speech into a general theory of genesis. Turning to later sections of “Plato’s Pharmacy,” Senatore convincingly shows that what Derrida sought to uncover was the irreducibility of writing or the anagrammatic structure of the text is itself an even more general geneticism. This is how we should understand Derrida’s famous interpretation of the signifier pharmakon: its inscription in Plato’s text makes it the untranslatable site of a condensation of multiple, contradictory meanings that are necessarily obscured in the moment of translation. Senatore quoting Derrida writes, “The effect of such a translation is most importantly to destroy what we will later call Plato’s anagrammatic writing…and, in the end, quit simply of the very textuality of the translated text” (37). Platonism is then the attempt to suppress the effects of the written trace, which necessarily carries with it these possible deviations and disseminations, “the irreducible synthesis of grammatical concatenations and stories that make up the grapheme pharmakon constitues the very element of Platonism, the vigil from which it wishes to dissociate itself” (37). We see again that writing, the process of inscription itself, cannot be seen as a derivative or secondary moment in the production of meaning, as if we passed simply from intention to expression in language, but rather meaning is the effect produced by writing. And since writing is taken as the general condition of the production of meaning this means that it necessarily carries within itself, from the very start, the irreducible possibility of its going astray as its essential possibility. Logos spermatikos and logos-zoon are then both attempts by Platonism to neutralize the necessary and aleatory effects of writing, which are in fact the minimal conditions of possibility of all beings: “…the grapheme-seed is the element of linguistics, zoology, politics, and thus of all regional discourses” (44).

Senatore’s second chapter on Platonism turns to a reading of the Derridean notion of khora as developed in Derrida’s reading of Plato’s Timaeus. Senatore here makes extensive use of Derrida’s unpublished seminars from 1970-71 (Theory of Philosophical Discourse: Conditions for the Inscription of the Text of Political Philosophy—The Example of Materialism) and 1985-86 (Comparative Literature and Philosophy: Nationality and Philosophical Nationalism). What is at stake is pushing this previously elaborated thinking of writing to its extreme by considering its implications for the notion of origin. It is a question of going beyond the opposition of paradigm/copy or father/son to what precedes and makes possible oppositionality as such. Philosophy, as Derrida suggests in the 1970-71 seminar, deals exclusively with the oppositional, but is not able to think what makes oppositions possible in the first instance. But khora names the very condition of these oppositions in general, the very possibility or opening for beings. Quoting Derrida’s unpublished seminar we read, “Being absolutely figurable, the receptacle escapes all figures, it does not let itself be captured by any figure and necessarily exceeds the trope or the representation that are intended for it [qu’on lui destine]” (60). Senatore will then connect this to Derrida’s final essay on khora wherein the originary opening and receptivity that this Platonic notion is meant to designate is thematized as the minimal condition for understanding history: history is possible only on the basis of the originary openness that khora names, that is, the empirical succession of events that we call history, wherein all thing come to be called historical, presupposes precisely this originary opening and condition of possibility, this formlessness that gives form. And it is here that Senatore suggests that Derrida discovers in Plato’s text a thinking of history irreducible to Platonism. We are no longer thinking in terms of generational succession, of direct and risk-free intergenerational transmission, but rather thinking on the basis of something—though certainly not a being— pre-originary, or as Derrida writes “before and outside all generation” (67). This thinking of the pre-originary, as Derrida understands it, is both the unthought of philosophy, what cannot be thought in the discourse of philosophy, but also philosophy’s necessary excessiveness: “Khora withdraws from the field of philosophy, as meta-philosophical necessity that remains unheard-of or is removed, that bears within itself another thinking of history, the only thinking of the concept and historicity of history” (68).

In the final three chapters Senatore moves on to discuss Hegelianism, that is, Hegel’s philosophical considered as the most radical attempt to think through the textuality of philosophical language that Platonism had denied in order to constitute itself as philosophical discourse (69). Now, according to Derrida in his 1969-70 seminar, his goal is to call “into question what constitutes the essence and telos of philosophy, that is, holding [tenir] the most general discourse, and thus the most independent one, in relation to which particular discourses (determinate domains) would be hierarchically ordered” (70). In other words, it will be an attempt to show the impossibility of philosophy constituting itself as a completely originary and independent discourse, that is to say, one which makes no recourse to metaphoricity or language imported from other discourses. This will in turn make possible a criticism of philosophy as the most general discourse whose task it is to order regional discourses and produce “the sense of sciences” (73). In this way, the concept of life and life of the concept in Hegel repeat the Platonic logos-zoon, which makes not biological reproduction the foundation of all transmission and generation, but rather biological reproduction is understood on the basis of the philosophical logos spermatikos wherein life is understood as “the generation of consciousness and thus as the nonmetaphorical and originary relation between the father and the logos-zoon, as the removal of the mother, self-reproduction, etc.” (73-4). To affirm against this position the Derridean thinking of dissemination or the anagrammatic structure of writing is tantamount to “pointing to a minimal structure (or an element) that would be diffracted into the transcendental signification and the natural one, and thus would remain behind their difference” (79). To think the textuality of the text is thus what Hegel gets closest to doing—after all Hegel is declared in De la grammatologie the last thinker of the book and the first thinker of writing[xii]—when reflecting upon the speculative nature of the German language, that is, its ability to think with words whose meanings are antithetical. Hegel would then be the first philosopher to consciously accept and affirm the anagrammatic structure that Plato repressed when faced with signifiers such as pharmakon. Aufhebung, for example, is the metaphorical hinge that binds the concept of life and life of the concept together, but what Hegel precisely risks is reducing the generation of life to the generation of the concept and consciousness, in turn repeating the Platonic structure: “the process of Aufhebung, which he [Derrida] understands as the scheme of the organization as well as the development of the Hegelian system, accounts for the solution of the equivocity of philosophical language” (88). In other words, the speculative identity that the signifier Aufhebung establishes between life, concept, and consciousness reduces the irreducible equivocity of language as inscription, of the anagrammatic structure of writing, or the textuality of the text.

Turning to Hegel’s explicit usage of the term germ (der Same), from which the book gets it title, Senatore focuses on Derrida’s reading of Hegel’s natural images and metaphors. It is again the speculative identity between life and concept that allows Hegel to see the movement of the concept as analogous to the development of life from seed to organism that then goes onto produce more seeds. The seed alienates itself in the process of its very development only to return to itself. Hegel’s system functions by building larger and more comprehensive accounts of this same developmental process since spirit too is self-reproducing and returns to itself as shown in the Phenomenology of Spirit. This discussion continues to include Hegel’s image of the family tree and the book of life, in various texts such as The Spirit of Christianity and its Fate and Reason in History. Again, what is at stake is the apparent covering-over by Hegel of his discovery of an irreducible difference, a remainder or excess, that cannot be included into the movement of the concept-life. Senatore goes on to discuss Derrida’s treatment of this issue in the opening text of Dissemination, which questions the role of the preface as traditionally understood. Derrida’s most experimental writing practices were developed in this period as the unorthodox opening “preface” of Dissemination bears many relations to the form and content of Derrida’s Glas that would be published two year later following the contemporaneous seminar La Famille de Hegel. If the traditional preface is intended to prepare the reader for what is to come, to make the future present at the outset, Derrida’s text is meant to draw attention to the work of dissemination as an irreducible or minimal structure as such. Senatore writes: “Dissemination is the name given to a project that he [Derrida] has started elaborating in “Force and Signification…and further developed in Of Grammatology, where he thinks of writing as the general structure of genesis and thus as the element [or minimal structure] of history and life” (132-33). Dissemination is thus what cannot be appropriated in the self-movement of the concept or life since it is the latter’s irreducible condition of possibility. Meaning, as Derrida discovered in Husserl, thus cannot be signaled or indicated in advance (by a preface or pre-text), but must awaits its moment of empirical inscription or embodiment as an “irreducible delay” that Hegel describes as an “external necessity” (121). The preface is then the attempt made by philosopher’s to suture this originary structure of delay that is immanent and necessary to the unfolding of the concept, an attempt to reduce this essential “out-of-jointness” by making the sense of what is to come present in the present, that is, at the origin.

The preface to Hegel’s Science of Logic perfectly encapsulates this tension: it both does not proclaim in advance what is to come, since logic, for Hegel, can only emerge at the end of the text and cannot be seen as an empty formal method that is discovered at the outset and applied throughout. Yet this admission makes the preface itself superfluous in some sense since it is external to the work itself and is excluded from the immanent unfolding of the concept, that is, from the logic itself. But Derrida wants to read this double status of the preface as being itself a figure of the structure of genesis in general, as that element that resists being folded into the logic of the text itself, and yet is structurally necessarily. This discussion leads Senatore to directly address Derrida’s reading of François Jacob’s La Logique du vivant from the unpublished seminar La Vie la mort. Indeed, Derrida’s “Outworking, Prefacing” is thus the “protocol for a non-Hegelian and non-genetic understanding of genesis” (135). Jacob addresses directly, by way of Claude Bernard, the way in which modern biology has reconciled the contradiction between scientific explanation and teleology: the notion of “genetic programme” allows Jacob and other modern biologists to think the developmental logic of an organism as it follows out genetic instructions inscribed in itself. Heredity viewed as a coded program in chemical sequences dissolves the paradox. But for Derrida, this is not the problem. Whether divine creator or genetic inscriptions, both appeal to and are determined by the logos spermatikos insofar as modern biology posits a preformationism without intention. In other words, dissemination, inscription, anagrammatic writing and textuality are once again repressed.

Senatore’s book then quickly concludes by turning to Derrida’s writings on philosophy, philosophical education, and teaching, which were written during a time when educational and pedagogical reforms were being proposed in France. But in the provocative final pages, Senatore analyses Derrida’s reading of Marx in an unpublished GREPH seminar where it is suggested that ideology is produced necessarily as a result of the originality of sexual difference and thus belongs to the “space of biological and natural life” and not to the superstructure as Marxists have typically held (144).

*****

I began this review by suggesting that what makes Senatore’s book so valuable is its insistence on Derrida’s thinking of a general or minimal structure of genesis, and that recent scholarship on Derrida, which is of a very high quality, also has been seeking to reclaim Derrida as an authentic philosopher against the many decades he was appropriated as a literary theorist and critic, a post-modern or post-structuralist thinker of the insuppressible play of meaning and language or who celebrates the absence of universals or essences. Indeed, I think these new readings are not only correct, but necessary. They find in Derrida a strong and essential thinking of what is necessary, or, a thought of the necessary minimal structures and conditions for the existence and experience of beings as such. Senatore’s claim is that Derrida thinks a general or minimal theory of genesis as such, one that accounts for the genesis of anything whatsoever, from cultural products to biological organisms. Yet throughout Senatore insists on the “nonphilosophical”[xiii] nature of Derrida’s deconstruction insofar as it is non-genetic or breaks with the classical idealist conception of the logos spermatikos. But what precisely is nonphilosophical about uncovering an absolutely general condition to which all beings are necessarily submitted? Or making clear this minimal element that is presupposed not only in all previous philosophical discourses, but also in all scientific discourses? Even if this condition is paradoxical, self-effacing, or never fully present. This strikes me as a quite typical gesture of transcendental philosophy, which is constantly seeking more and more minimal, but absolutely necessary structures, that all beings (cultural, biological, or otherwise) conform to in all cases. Recent French thinkers have even pushed this further, for example, Michel Henry, who claims that the supposedly originary difference of someone like Derrida or Deleuze in fact presupposes an even more originary identity or presence that he calls “life.” At the same time, however, Senatore quotes from unpublished seminars where Derrida seems acutely aware of this problem and criticizes philosophers for attempting to organize and hierarchize all other discourses in an attempt to theorize the meaning of sciences in general. Indeed, this was the general problematic of phenomenology in Husserl and Heidegger that Derrida was steeped in and in many way ways continues and radicalizes. This, as I understand it, is Derrida’s insight in his La via la mort seminar, namely, that the biological sciences must come to terms with a necessary condition-obstacle, namely writing, that they at once unknowingly theorize (since they had just begun to speak of a “genetic code”) and yet fail to thematize as such for if they were to do so their investigations would have to be fundamentally altered to account for the irreducibility of the trace structure. Only deconstruction provides such an insight and can think science’s unthought conditions of possibility-impossibility.

But there is another philosophical tradition that runs counter to the one that Derrida deconstructs most often, namely, materialism. Rarely does Derrida engage in-depth with Machiavelli, Spinoza, Althusser[xiv], not to mention Marx, Engels, and Lenin and other canonical “Marxist philosophers.” Derrida himself admitted to not understanding Spinoza[xv] and Warren Montag has argued that this supposed distance covers what is in fact an extreme proximity.[xvi] In other words, my hunch is that precisely what Senatore calls the “nonphilosophical” is what, in other circles, simply gets called materialism or to be more precise, and borrowing an expression from Althusser, aleatory materialism. Indeed, Althusser had proposed, in his innovative reading of Marx and Spinoza, as early as 1966 (if not earlier), a renewed materialist conception of the “encounter” [“théorie de la rencontre”] or of “conjunction” [théorie de la “conjunction”] that is fundamentally different from the genetic theory of genesis.[xvii] This thought of a non-genetic genesis was also at work in Machiavelli and Spinoza, Freud too, when he theorized the overdetermination of dream elements. And Althusser will later seek to establish an entire “underground current” of thinkers who belong to this materialist tradition.

None of this is to suggest that Senatore is unaware of these issues. On the contrary, I take it that Senatore is in fact pushing Derrida in the direction of productive encounter with thinkers like Althusser and philosophical materialism more generally. And this potential encounter to come is perhaps the one best suited for re-thinking the relationship between philosophy and science, that is, to break with the tradition that Derrida has identified according to which it is the task of philosophy to make sense of the sciences for them or to assign to them their ultimate meaning. But to what extent does this effort in Derrida remain restricted, if not stifled, by his Husserlian inheritance? Or by transcendental philosophy more generally? These are questions that I hope will spur further consideration and future philosophical inquiry and Derrida’s inclusion in these debates is highly anticipated.

[i] De la grammatologie (Paris: Éditions de Minuit, 1967), pg. 19

[ii] See in particular Malabou’s 2005 book La plasticité au soir de l’écriture (Éditions Léo Scheer) as well as her 2004 Que faire de notre cerveau? (Bayard) and more recently Ontologie de l’accident: Essai sur la plasticité destructrice (Léo Scheer, 2009), Avant demain. Épigenèse et rationalité (PUF, 2009) and Métamorphoses de l’intelligence: Que faire de leur cerveau bleu? (PUF, 2017).

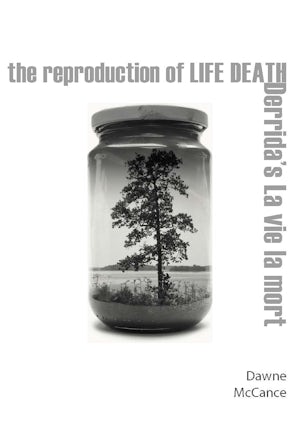

[iii] I have in mind not only Senatore himself, but also Francesco Vitale, whose 2018 book Biodeconstruction: Jacques Derrida and the Life Sciences (SUNY) was translated by Senatore, but also the work of Dawne McCance who is preparing a book on this seminar and has been publicly lecturing on it for some time now.

[iv] The Derrida Seminars Translation Project, consisting mainly of Peggy Kamuf, Geoffrey Bennington, Elizabeth Rottenberg, David Wills, Michael Naas, and Pascale-Anne Brault, has published translations of Derrida’s final two seminars The Beast and the Sovereign and The Death Penalty, as well as an early seminar on Heidegger and an 1970s seminar Theory and Practice. The English language translation team is also now in charge of preparing the French manuscripts for publication, which will mean a faster rate of publication in both French and English. The La vie la mort seminar will soon be published in French by Éditions du Seuil in the new series “Bibliothèque Derrida”, having been edited scrupulously by Pascale-Anne Brault and Peggy Kamuf. The English translation has already been completed by Brault and Michael Naas and is forthcoming with the University of Chicago Press.

[v] François Jacob, it will be remembered, along with Jacques Monod and André Lwoff, won the nobel prize for medicine in 1965 and wrote La Logique du vivant as a kind of vulgarisation of his award-winning discoveries. Monod will do the same in his book Le Hasard et la Nécessité: Essai sur la philosophie naturelle de la biologie moderne.

[vi] See, most recently, Paul M. Livingston’s excellent book The Politics of Logic: Badiou, Wittgenstein, and the Consequences of Formalism (Routledge, 2012) or Christopher Norris’ Derrida, Badiou, and the Formal Imperative (Bloomsbury, 2014).

[vii] The major early philosophical reading is no doubt Rudolph Gasché’s The Tain of the Mirror: Derrida and the Philosophy of Reflection. Gasché explicitly writes in the opening pages, “Indeed, Derrida’s inquiry into the limits philosophy is an investigation into the conditions of possibility and impossibility of a type of discourse and questioning that he recognizes as absolutely indispensable” (2).

[viii] For example, in the work of Slavoj Zizek, Adrian Johnston, Frank Ruda, Rebecca Comay, and others.

[ix] The author of the present review had the honor of working on the translation of the first half of this seminar with the Derrida Seminars Translation Project in July 2017.

[x] Indeed, this paradoxical quasi-scientific character, or non-philosophical scientific character of deconstruction was precisely Derrida’s discovery in reading Husserl, namely, that phenomenology is necessarily led to posit writing as the most minimal condition for the historical transmission of ideal meaning, but in so doing, is forced to study a non-present “object”, that is to say, one that puts into question the very notion of objectivity as such. Derrida reiterates this logic in the beginning of the section “De la grammatologie comme une science positive”, where he suggests that the possibility of grammatology being a science, a science of writing or traces, rests upon its own impossibility since it would shake or make tremble (ébranler) the very concept of science itself (see page 109).

[xi] My translation.

[xii] De la grammatologie, pg. 41. This quotation is preceded by the claim that Hegel, despite appearing as, in some sense, the metaphysical teleological thinker par excellence, he is “also the thinker of irreducible difference.”

[xiii] Senatore uses this language on pages xii, 57, 63, 69, and 143.

[xiv] The recent publication in French and forthcoming translation of Derrida’s 1976-77 Théorie et pratique seminar certainly changes this. But for as much as Derrida engages with Althusser here, the seminar ultimately turns on a reading of Heidegger and the question of techne.

[xv] “Dialogue entre Jacques Derrida, Philippe Lacoue-Labarthe et Jean-Luc Nancy.” Rue Descartes 2006/2 (no. 52), pg. 95.

[xvi] “Immanence, Transcendence, and the Trace: Derrida Between Levinas and Spinoza.” Badmidbar: a Journal of Jewish Thought and Philosophy, 2, Autumn 2011.

[xvii] See Althusser’s text from September 1966 “Sur la genèse”, where he explicitly attacks the genetic theory of genesis where the result is contained “en germe” in the origin. Available through décalages:

https://scholar.oxy.edu/decalages/vol1/iss2/

The Reproduction of Life Death: Derrida’s La vie la mort

The Reproduction of Life Death: Derrida’s La vie la mort