Hannah Arendt: Between Ideologies

Hannah Arendt: Between Ideologies

International Political Theory

Palgrave Macmillan

2020

Hardback 77,99 €

X, 258

Hannah Arendt: Between Ideologies

Hannah Arendt: Between Ideologies

Across the Great Divide: Between Analytic and Continental Political Theory

Across the Great Divide: Between Analytic and Continental Political Theory

Thinking with Adorno: The Uncoercive Gaze

Thinking with Adorno: The Uncoercive Gaze

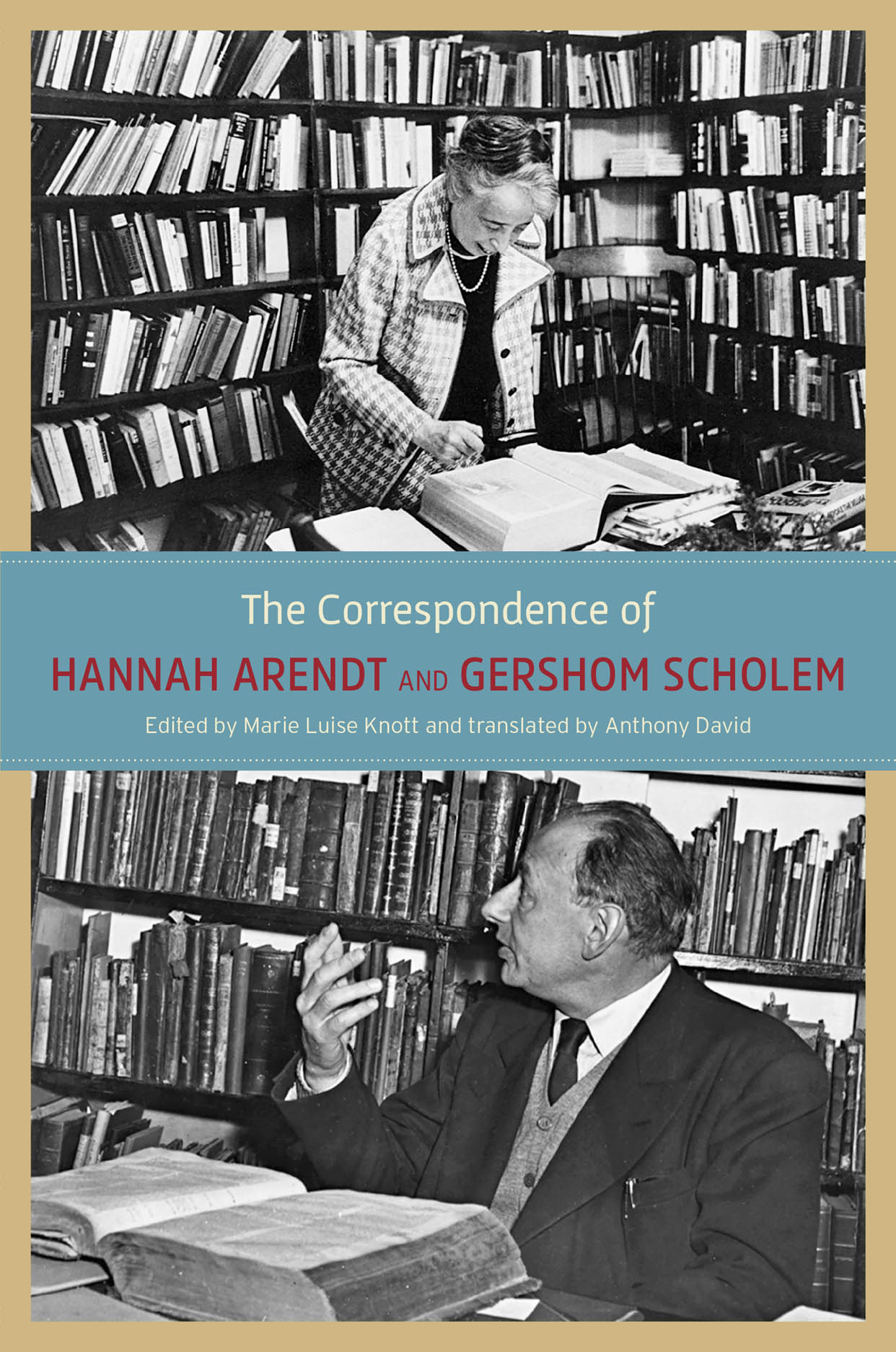

The Correspondence of Hannah Arendt and Gershom Scholem

The Correspondence of Hannah Arendt and Gershom Scholem

Reviewed by: Michael Maidan

Those familiar with the names of Hannah Arendt and Gershom Scholem are likely aware that they were on opposite sides of the polemics around Arendt’s book on the Eichmann trial. But they may be less acquainted with the extent of the intellectual and deep personal relationship between them. As it is explained in Marie Luise Knott’s useful ‘Introduction’ to this volume, only when we take into consideration the whole series of letters that they had exchanged over the years, ‘does a fuller portrait of their friendship emerge’ (vii). The value of this exchange is not merely biographical. Both Arendt and Scholem witnessed, at times participated in, and overall reflected on some of the more dramatic events of the first half of the 20th century. Their reflections at time intersected, and at time influenced each other, sometimes in imperceptible ways.

In 1963, Gershom Scholem wrote to Hannah Arendt a letter harshly condemning Arendt’s positions in her recently published Eichmann in Jerusalem. The controversy created by her book and its influence on the life and work of Arendt was recently dramatized in Margarethe von Trotta’s film Hannah Arendt (2012).

Scholem points out that Eichmann’ in Jerusalem really deals with two subjects: (1) Jews and their behavior during the Holocaust (Scholem writes: the ‘Catastrophe’); (2) Eichmann and his responsibilities (Letter 132, p. 201). Regarding the question of the behavior of the Jews, Scholem mentions the many years which he devoted to this question, and not just in the context of the Holocaust, but the course of Jewish history in general, and its prior catastrophes. On this question, his position is that:

There are aspects of Jewish history (and this is what I have occupied myself with for the past fifty years) which are hardly free of abysses: a demonic decay in the midst of life; insecurity in the face of this world (in contrast to the security of the pious, whom your book, bafflingly, does not mention); and a weakness that is perpetually confounded and mingled with trickery and lust for power. These have always existed, and it would be odd indeed if they didn’t come to the fore in some form at times of catastrophe (201).

Scholem intimates that this is indeed an important and grave subject, much more important thanthe question why the Jews did not defend themselves against the Naziaggressor. But, we lack the required historical perspectiveto address this subject. He finds that Arendt in her book ‘addresses only the weakness of Jewish existence’, and that to the extent that weakness there was, her emphasis was ‘completely one sided’ (201). Furthermore, her account obscures the problem. The form of the narrative substitutes itself for the content. It is Arendt’s language, more than the content itself that makes people angry with the book. Scholem points out to the ‘lighthearted style, by which I mean the English word “flippancy,” that you employ all too often in your book. It’s inappropriate for your topic, and in the most unimaginable way.’ But, if Scholem finds parts of the book frivolous, it is, first and foremost, because of a ‘lack of love of Israel’, a lack of empathy for her own people, which Scholem claims is quite common among Jews which had been members of the Left.

Arendt replied with a letter that curtly dismisses Scholem’s criticism. She rejects as uninformed the idea that she had ever been a member of the Left (Letter 133, p. 205). And regarding the more general claim that she lacks ‘Ahavat Israel’, Arendt responds unambiguously that she never hides the fact that she is Jewish: ‘That I am a Jew is one of the unquestioned facts of my life’ (206). But, for Arendt this fact belongs to the realm of the pre-political. She cannot refrain herself from antagonizing Scholem and asking about the history and meaning of ‘Ahavat Israel’ (love of Israel), a question that certainly would not contribute to mend fences with Scholem. She goes on and rejects the notion of love to a collective or to an abstract idea. She finds the idea of ‘loving of Israel’ baffling, as if loving herself, something that she claims to find impossible.

This exchange of letters and their publication by Scholem ended thirty years of mostly epistolary relationship between the political thinker and philosopher and the leading scholar of Jewish mysticism and kabbalah. Between 1939 and 1964, Hannah Arendt and Gershom Scholem exchanged close to 140 letters, ranging in content from the mundane to dealing with the tragic events of the thirties and forties, and to their early efforts for the salvaging and reconstruction of the remains of Jewish communities of Western and Eastern Europe after the Holocaust.

Walter Benjamin first brought them together. And Benjamin’s tragic death, the fate of his unpublished work, and the pious will to eventually publish his work and rescue it from oblivion cemented their relationship and is an invisible thread stitching the letters together.

In the immediate postwar period, both Arendt and Scholem were personally involved in a complex process to reclaim the Jewish cultural heritage from the ruins of Europe. Many letters in this volume reflect their travails in this period, ranging from official memorandums to more personal letters in which they exchange information about the progress in their joint work.

Arendt and Benjamin became friends during their exile in Paris. Arendt fled to Paris in 1933, after having been briefly detained by the German police. The same year Benjamin left Germany, first for Paris and then for Ibiza, returning finally to Paris. Some of the earliest letters in this book refer to Benjamin. Letter 1 makes this shared connection clear:

I’m really worried about Benji. I tried to line up something for him here but failed miserably. At the same time, I’m more than ever convinced how vital it is to put him on secure footing, so he can continue his work. As I see it, his work has changed, down to his style. Everything strikes me as far more emphatic, less hesitant. It often seems to me as if he is only now making progress on the questions most decisive for him. It would be awful if he were to be prevented from continuing. (3)

Letter 4 shows the confusion and hopelessness of the refugees, trying to make sense of the defeat of the French army and the capitulationof the Third Republic. Writing from New York, Arendt shares with Scholem the information she has about Benjamin’s suicide, and the events preceding the tragic outcome. The letter ends with a reference to a question that will surface again and again in the correspondence: the fate of Benjamin’s literary estate, who has it, and to whom it belongs. To ponder on those questions at that time may seem totally irrelevant as Benjamin was virtually unknown outside of Germany. The undercurrent to this preoccupation is, at that point, Arendt and Scholem antipathy for Adorno (referred in this letter by his real last name: Wiesengrund), and their suspicions that the Institute for Social Research will try to bury Benjamin’s legacy deep into their archives.

In letter five, Scholem complains to Arendt of the lack of response from Horkheimer and Adorno to his questions regarding Benjamin’s estate. In letter seven, Arendt tells Scholem of the small mimeographed homage to Benjamin prepared by the Institutein 1942. She notes that the only part of the estate that it contains is the Theses, a copy of which was given to Arendt by Benjamin. Scholem in the following letter complains of not having received anything from anybody. Arendt replies promising to send Scholem her only copy of the Theses and refers to her conversation with Adorno and with Horkheimer. The latter confirmed to her that the Institute has a crate with Benjamin papers, that they are kept in a safe, and that the Institute does not know what is inside, something that Arendt does not believe to be true. The same complaints return time and again throughout the correspondence. Their misgivings are not only consequence of misinformation (Benjamin entrusted several of his manuscripts to friends in Paris, and some were only recovered in recent years, while other papers were apparently lost or destroyed) but also ideological suspicion. Scholem makes it clear to Arendt that he believes that Horkheimer’s analysis of antisemitism—probably a reference to Horkheimer’s 1939 The Jews and Europe —is ‘an impudent, arrogant, and repulsive load of nonsense without a shred of intelligence or substance’ (20). In another letter, Arendt mentions to Scholem that ‘meanwhile, the [American Jewish] Committee has charged Mr. Horkheimer with the task of battling anti-Semitism. Putting the fox in charge of the henhouse is only one of the many amusing aspects of the story. Incidentally, aside from his repulsiveness, Horkheimer is even more half-witted than even I had thought possible.’ (Letter 13, p. 25). This is a reference to the project which resulted in the publication by Adorno and others of The Authoritarian Personality (1950), and of several monographies on the nature of antisemitism and authoritarian tendencies in general and in America in particular.

Several letters in the late 1940’s deal with a failed attempt to bring an edition of Benjamin collected writings in English. While Arendt agreed to put together the volume, she declined to write an introduction and requested one from Scholem. After invoking different excuses, she gets to the real issue: ‘I still haven’t been able to come to terms with Benjamin’s death, and therefore over the subsequent years I’ve never managed to have the necessary distance one needs to write “about” him’ (72). Indeed, she will only write about Benjamin in the short introduction to her edition of his collected works in English, published in 1968. Benjamin collected works were finally published in 1955 in Germany, edited and introduced by Adorno (Letter 112, p. 183), followed by an edition of his letters, edited by both Scholem and Adorno.

Many of the letters document Arendt’s and Scholem’s involvement with efforts to rescue Jewish cultural and religious objects that were looted by the Nazis and stored in different locations, particularly in what become the American military occupation zone. Arendt participated in this effort as Executive and Field director of CJR, Inc., a not for profit organization which acted as cultural affairs executor for the Jewish Restitution Successor Organization (JRSO), an organization established by the leading Jewish organizations in the US, Mandatory Palestine, Britain and France to assist in the restitution of ownerless Jewish property in Germany and the occupied countries of central Europe. The ‘Introduction’ presents a detailed reconstruction of this period in Arendt’s life that is not well documented in her standard biography by Young-Bruehl.Arendt involvement started with a study about the Nazi’s policies to pillage and destroy Jewish culture commissioned by historian Salo Baron 1942. In her study she documented not only the pillaging in Germany and Austria, but also in occupied Poland and France. She later worked between 1944-1946 as a researcher in the European Jewish Cultural Reconstruction (CEJCR), an organization created by Baron. Her task was to gather information and prepare a list of Jewish cultural organizations existing in axis-occupied Europe, which included also information on the properties owned by these institutions. Three years later, Baron hired Arendt as executive secretary of a successor organization, the JCR.

If Arendt’s role in the work of the JCR was at the organizational level, Scholem participated as a scholar of Judaism, as an individual personally familiar with the holding of the major Judaic libraries in Europe before the war, and as a representative for the Hebrew University in the just recently established State of Israel. Benjamin wrote in his Theses on the Philosophy of History (a copy of which he entrusted with Arendt before his failed attempt to cross the French-Spanish border) that ‘even the dead will not be safe from the enemy if he wins. And this enemy has not ceased to be victorious’. Scholem’s and Arendt’s efforts, as well as the efforts of their many partners in this mission, were directed to prove Benjamin wrong on this count, by rescuing whatever could still be rescued, and by making sure that the intellectual and cultural treasures recovered did not become mere archaeological remnants but played a renewed role in a living history.

This section of the letters alternates between the businesslike to the personal. Accordingly, someof the lettersare formal, others relaxed and friendly. Some, combine both aspects. In letter 5, Arendt reports on different matters related to their common work in JCR, but then the letter ends with a copy of an early poem by Benjamin. While a detailed study of these letters will only be of real interest for an historian of the post-war Jewish communities in Europe, even a superficial reading conveys both the gloom and the determination of those involved in this project to do whatever possible to salvage the material remains of European Jewish culture. The book includes also four extant field reports (Number 12 through 18) and a final report to the JCR Commission.

In a letter from 1942, Scholem informs Arendt that his book Major Trends in Jewish Mysticism has been recentlypublished, and copies sent to United States. He asks Arendt to read the book and invites her comments, not as an expert in the subject matter, but as a ‘reflective reader’. Two years later Arendt mentions having sent a review to the journal Menorah (276, note 4), which she claims she wrote for Scholem’s eyes, but decided to publish because, even if she felt inadequate to the task, other readers would have been even less adequate (22). The review was never published, and the manuscript apparently did not survive. Arendt will have the opportunity to discuss the revised second edition (1946), in her Jewish History, Revised (1946). Arendt reads Scholem’s metahistorical conclusions drawn from the history of Jewish Mysticism in the light of her own hypothesis about the failed nature of Jewish emancipation and assimilation to the majority cultures of Eastern and Central Europe which she elaborated in her biography of the Berlin Jewish salonnière, Rahel Varnhagen and in her essay ‘The Jew as Pariah: A Hidden Tradition’ (1944).

Arendt’s critical assessment of Jewish emancipation brings into play three ideal types of modern Jews: the pariah, the parvenu, and the conscious pariah. She adopts from Max Weber the notion of pariah peoples, i.e., ethnic minorities characterized by a specific social and economic role and kept separated from mainstream society. But she does notconduct her analysis on sociological, economical or historical terms, but through the mediation of literary characters which incarnate these ideal types. Hence her reliance on Heine and Kafka, which represent—according to her interpretation—forms of rebellion against the pariah status and of rejection of the ways of the individualistic parvenu. These thinkers and artists reject assimilation, including assimilation by identification with revolutionary struggles, as many Jews did in the early 20th century. Arendt concludes her essay with the following reflection, which exposes the tensions within her view of politics:

only within the framework of a people can a man live as a man among men, without exhausting himself. And only when a people lives and functions in consort with other peoples can it contribute to the establishment upon earth of a commonly conditioned and commonly controlled humanity (Arendt, The Jew as Pariah: The Hidden Tradition, Jewish Writings, 2007, 297).

Scholem is skeptical. He rejects Arendt’s interpretation: ‘I’d really like to lead off with a discussion of your thesis of the pariah’ he writes to her and adds: ‘to my inner “Rashi”—a reference to one of the most important medieval rabbinical interpreters of both the Bible and the Talmud—the texts speak a different language’. He adds that ‘in order to squeeze them into the concepts you employ you end up leaving many things out that don’t fit.’ (24). He rejects Arendt’s interpretation of Heine and Kafka, two authors and are central to Arendt’s thesis. But Scholem excuses himself of any detailed discussion, adducing exhaustion and lack of energy at that time to engage in any serious intellectual dispute.

The intellectual, political and emotional differences between Arendt and Scholem emerge clearly in their disagreements about the nature of Zionism. Arendt seems to believe that Scholem is close to her position or at least understands sympathetically her point of view. On close reading, nothing seems to be farther from the truth.

Arendt’s criticism of Zionism is twofold. She criticizes the transformation of the Zionist idea into an ethno-political nationalism. On this point, she feels close to Scholem’s ideas of a cultural Zionism. Her other criticism relates to the strategy of the Zionist movement vis a visthe Palestinian Arab population. Also, in this matter she felt that she could expect a warm interlocutor in Scholem, who was one of the founders of the short-lived Brit Shalom (Peace Alliance) movement, who advocated for Jewish and Arab peaceful coexistence in Palestine. Her main essay on this matter was published in 1944, under the title ‘Zionism reconsidered’. In her article, she criticizes the positions adopted in by ‘the largest and more influential section of the World Zionist Organization’in 1944, advocating the establishment of an independent Jewish national state in Palestine. Scholem’s reply comes in a letter from early 1946, several months later. He thanks her for the paper, but expresses his concerns about her essay, which he dismisses outright. ‘In vain I asked myself what sort of credo you had in mind when you wrote it’ he,writes. ‘Your article has nothing to do with Zionism but is instead a patently anti-Zionist, warmed-over version of hard line Communist criticism, spiced with a vague Diaspora nationalism’ (42). He continues refuting each of Arendt’s central claims in a detailed way, concluding in a stern although amicable way.

Arendt replied a few months later. She first alludes to an attempt to publish some of Benjamin writings in English. After concluding the business that ‘the two of us can agree on’, she moves to their disagreements about Zionism. She first attempts to establish a ground level for their discussion, explaining her two main concerns. On the one hand, a rejection of any ideology or worldview, which she opposes to a ‘political standpoint’. She rejects ‘Zionism’ as an ideology but approves of Scholem’s decision to emigrate to Palestine (which is the practical content of the Zionist idea!). And while she rejects Zionism, she claims that her rejection is grounded in her concern with the Jewish settlement in British mandatory Palestine and not because of any ideology. Having established that, she proceeds to restate her arguments in Zionism Reconsidered, the main being her rejection of the concept of an ethnically based nation-state (49-50), the idea of the identity between state, people and territory. She even states that her opposition to the idea of a Jewish state is not limited to the issue of the Arab population and their opposition to such a Jewish state, but because a multinational state ‘is the most rational political organization’ (50). She also re-states her position regarding the failure of the Jewish organizations to stand behind the call for a Jewish supranational army combatting Germany alongside the allies, somewhat along the lines of the free armies of the German occupied countries that combated under their own uniforms within the allied forces.

Eichmann in Jerusalem: An essay on the banality of Evil markthe final break between Arendt and Scholem. To the letter we discussed earlier, Arendt replied with a strong rebuttal in Letter 133. Arendt rejects Scholem’s characterization of her as being a former leftist. She claims not be interested in her youth on history or politics, but only in philosophy. And that only recently she had the opportunity to study Marx. Furthermore, she claims to have never negated her Jewishness, which she interprets as a ‘brute fact’. Nevertheless, this does not translate, as Scholem’s seems to imply, into a form of generic solidarity with other Jews, what Scholem described as ‘Ahavat Israel’ (love or concern for the fate of other Jews). Arendt claims that she has never experienced such abstract love for any‘collective’. Furthermore, such ‘love’ would have been suspect to her, as a sort of self-love. She illustrates her point with an anecdote from a conversation she had with Golda Meir. Arendt expressed to Meir her concern about the lack of separation between the State and religion in Israel, whereas Meir answered that while she herself does not believe in God, she believes in the Jewish people. And Arendt adds:

This is a horrible comment, in my view, and I was too shocked to offer a response. But I could have replied that the magnificence of this people once lay in its belief in God—that is, in the way its trust and love of God far outweighed its fear of God. And now this people believes only in itself! What’s going to become of this? (207)

The underlying question is, as Arendt puts it clearly, one of patriotism. And for Arendt patriotism is not possible without criticism, i.e., without considering that ‘that injustice committed by my own people naturally provokes me more than injustice done by other’ (207). The letter addresses then a number of claims made against the book which she considers to be invalid: that she turned Eichmanninto a Zionist, that she asked why Jews in axis occupied countries did not defend themselves, that instead she really addressed the question of the collaboration of the Jewish appointed authorities during the period of the ‘final solution”, that if Jews had no material possibility to defend themselves in an active way, they should have embraced a policy of complete refusal to collaborate. The only point in which Arendt claims to agree with Scholem is Eichmann’s sentence. She agrees that it should have been carried out, even if she disagrees with most other issues. In fact, Scholem disagreed with the carrying out of the sentence (213).

The letter concludes with a discussion of the idea of ‘banality of evil’. Arendt explains her idea: evil is not radical, it is shallow, even if some sorts of evil can be extreme (209). She promises to develop later this idea, which she does, at least in part, in her study of Kant.

Scholem responds to Arendt’s option of non-collaboration in a long paragraph in Letter 135. Scholem observes that, first, such a notion is used by Arendt to create a moral and political yardstick that is totally unfounded: ‘By presenting as a feasible humane and political strategy, and not for individual Jews but for millions of them, you end up elevating into a kind of postfestum measuring stick of judgment’ (212). But he leaves open the door to a discussion of evil, which he interprets in terms of bureaucratization of behavior, although he makes clear that he believes that this idea is an unrealistic description of the actual events: “The gentlemen enjoyed their evil, so long as there was something to enjoy. One behaves differently after the party’s over, of course (214).

The next exchange of letters is cordial but more reserved. Finally, the exchange ends with a letter from Scholem announcing a trip to New York to speak on Benjamin at the Leo Baeck Institute. Did they meet? In any event, no further letter is extant.

Phenomenology of Plurality: Hannah Arendt on Political Intersubjectivity

Phenomenology of Plurality: Hannah Arendt on Political Intersubjectivity

Reviewed by: Maria Robaszkiewicz (Faculty of Arts and Humanities, Paderborn University)

A book analyzing Hannah Arendt’s phenomenological background thoroughly is long overdue. Arendt’s biographer, Elisabeth Young Bruehl, mentions one of very few occasions, when Arendt spoke about her method (Young Bruehl 1982, 405), revealing her inclination to phenomenology: “I am a sort of phenomenologist. But, ach, not in Hegel’s way – or Husserl’s.” What sort of phenomenologist was Arendt then? Many scholars struggle with her methodology and it even worried one of her greatest mentors, Karl Jaspers, who complained about the ‘intuitive-chaotic-method’ of her writings. But could it be that there was a consistent methodological framework behind an ostensible chaos? Is it possible that Arendt not only was ‘a sort of phenomenologist’, but a fully fledged representative of the second generation phenomenologists after Husserl and Heidegger – whose members include Sartre, Fink, Merleau-Ponty, Patočka and Lévinas –who transformed phenomenology? In her new book, Sophie Loidolt makes a strong case for an affirmative answer to both of these questions. Phenomenology of Plurality: Hannah Arendt on Political Subjectivity is a very challenging read but it is also a very rewarding book.

Loidolt aims to draw a phenomenology of plurality from Arendt’s work and to illuminate consequences of a politicized approach to phenomenology by doing so. A further objective of the book is to rethink Arendt’s connections to phenomenology, positioning her in the broader context of traditional and contemporary phenomenological discourse (2). Both these aims interweave in Loidolt’s book, where she reconstructs basic phenomenological notions in Arendt, referring mainly to classical accounts of Husserl and Heidegger. The result is a novel account of the phenomenon of ‘actualized plurality’ in Arendt’s writings. Loidolt connects actualized plurality to the activities of acting, speaking and judging, which through their actualization evoke different spaces of meaning, where multiple subjects can appear to each other. The book brings Arendt into dialogue with numerous phenomenologists, most notably Merleau-Ponty and Lévinas. Further, Loidolt places her reflections in the broad context of Arendt-scholarship, although she distances herself from some prevalent paradigms present in the contemporary debate: the line of interpretation informed by the Frankfurt School (Habermas, Benhabib, Wellmer, and others), the poststructuralist approach (Honig, Villa, Heuer, Mouffe and others), as well as from the treatment of Arendt’s oeuvre from a purely political perspective, hence ‘de-philosophizing’ her (4) (Disch, Dietz, Canovan, Passerind’Entrèves, and others). In contrast, Loidolt aspires to rediscover the philosophical dimension in Arendt, not by depoliticizing her work, but rather by emphasizing the coexistence of both aspects and the connections between them. This inclusive gesture resonates with Arendt’s unwillingness to belong to any club and, consequently, with the difficulty to ascribe her to one academic field rather than to another.

Loidolt begins her book by invoking her intention to illuminate the philosophical dimension of Arendt’s work without distorting it by ignoring its other dimensions and deriving from it her goal to unveil the philosophical significance of Arendt’s work through a phenomenological examination of the notion of plurality. Many texts within Arendt-scholarship simply adopt Arendt’s language – often full of beautiful and meaningful expressions – without supplying a deeper analysis of its content and context. This is not the case with Sophie Loidolt’s book. She does not just ‘talk the talk’, she also delves deep into the meaning of Arendt’s language. Loedolt’s expertise in phenomenology allow her to achieve this goal, which also contributes to the achievement of her broader aim to familiarize both phenomenologists with Arendt and Arendtian scholars with foundations of phenomenology. The complexity of Loidolt’s book lies in this twofold focus: at first glance, it seems that the reader should have an extensive background both in Arendt and in phenomenology – a combination, which, as the author admits, is uncommon (2 – 8) but Loidolt does not demand so much of her readers. She draws numerous parallels between Arendt’s theory and those of other philosophers, whose status as phenomenologists is less contested, and she also continually draws readers’ attention to methodological elements that lie at ‘the heart of the phenomenological project’ (e.g. 25, 75, 125, 176). This way, she completes the task of introducing Arendt to phenomenologists and of introducing foundations of phenomenology to the Arendtians masterfully. Although this approach means that the book is not an easy read, it is definitely worth the effort.

The book consists essentially of two parts: in the first part, Transforming Phenomenology: Plurality and the Political, the author elaborates on the relation between Arendt’s account and phenomenology, whereas in the second part, Actualizing Plurality: The We, the Other, and the Self in Political Intersubjectivity, Loidolt develops her own phenomenological interpretation of Arendt’s philosophy of plurality. Each part comprises three chapters, divided into numerous subchapters, which makes this complex text more reader-friendly. The book is easy to navigate: every chapter begins with a very neat summary of the previous contents and a preview of what is tofollow. As such, each piece of theory that we encounter in subsection is approachable and easy to situate within the overall framework of Loidolt’s study. The only potential editorial refinement that comes to mind would be to number subchapters and to list these in the Contents, especially since the author often refers to subchapters by its number (e.g. 3.2), but these are not to be found in the current layout of the book.

In the first chapter, Loidolt lays the foundation for her investigation by drawing on the primordial event of the emergence of plurality. She sets off by reconstructing Arendt’s critique of Existenz Philosophy and classical phenomenology, based mostly on her early writings from the ‘1940s. The author sketches Arendt’s argument against (or at least relativizing) phenomenological accounts of Husserl, Heidegger, Sartre, and Merleau-Ponty, as well as her take on Jaspers, who represents ‘all that is good about Existenz Philosophy’ (35). Through these moves of association and distinction, says Loidolt, Arendt formulates what can be described as ‘new political philosophy’ (39-40) – even if Arendt herself would have considered this a contradiction in terms. Arendt had good theoretical reasons to renounce philosophy altogether, but since Loidolt aims at recovering the philosophical profundity of her thought, this term seems to be acceptable in this context. The key elements of the new political philosophy would then be a focus on the being-with dimension of human existence (42), a refusal to engage in the project of mastering once being (26, 44), and hence also underlining the fragility of the realm of human affairs (46). These elements resonate with central categories of Arendt’s account of the political: plurality, freedom, and natality.

After having ‘provided a point of departure for a phenomenology of plurality’ (51), in the second chapter Loidolt puts actualizing plurality in a space of appearance in the center of her reflection. She emphasizes its active character as a contingent, non-necessary event and identifies it as a core phenomenon of Arendt’s new political philosophy. The chapter consists of an analysis of three central notions that indicate Arendt’s affinity to phenomenological approach: appearance, experience, and world. Each section traces one of the aforementioned notions back to its origins and shows its relevance for the project of the new political philosophy. First, Loidolt explores the notion of appearance, establishing, with Villa, its status as constitutive of reality (55). Through illuminating this ontological status of appearance in Arendt, Loidolt proves her to be a phenomenologist at heart: Arendt insists on exclusive primacy of appearance, an idea that she gets primarily from transforming Husserl’s and Heidegger’s phenomenological accounts and not, as Villa and Beiner argue (55), from Kant. Following Cavarero’s claim that Arendt’s political theory implies a radical form of phenomenological ontology, Loidolt retraces Arendt’s project of pluralization of appearance (64) and unfolds its consequences for her understanding of reality, self and world, referring in the course of her analysis to Husserl, Heidegger, and Merleau-Ponty. Additionally, the author supplies a table relating respective concepts in Husserl, Heidegger, and Arendt that allows readers to follow the depicted transition at a glance. The second section focuses on the notion of experience. Loidolt offers a short overview of phenomenological-hermeneutic takes on Arendt’s notion of experience, but also investigates the deeper level of her engagement with experience, which goes beyond Arendt’s ‘techniques’ of narration, interpretation, and storytelling and concerns the very structure of experience (76). In the subsection devoted to this deeper level, she links Arendt’s historical hermeneutics to the phenomenological tradition, evoking not only Husserl and Heidegger, but also Lévinas, Merleau-Ponty, Patočka and Fink, and points at the interconnected notions of intentionality and subjectivity, which constitute the structure of experience. She shows how experience in Arendt is being actualized and pluralized, so that experiencing subjects can be conceived as ‘essentially existing as enactment’ in their multiplicity, hence transforming them into a moment of actualized relation (84, 93). The third section discusses Arendt’s concept of the world. Loidolt draws our attention to three notions of the world present in Arendt’s writings: the appearing world, the objective world, and the with-world (93). In her phenomenological analysis (turning again to Husserl and Heidegger), Loidolt displays the interrelation of these three notions and how they build upon one another. Indeed, the notions of the world as the space of appearance and the space of the political (with-world) are often used interchangeably in the literature. Loidolt’s phenomenological perspective contributes greatly to a more nuanced understanding of the difference between the two, which proves to be quite fundamental. Throughout the three sections, Loidolt constructs the ‘pluralized and politicized’ phenomenological account that Arendt, according to her, had in mind. By doing so, she reaches out to both her target groups: Arendt-scholars and phenomenologists. She shows, on the one hand, that a phenomenological perspective can provide a better and more thorough understanding of Arendt’s theory, without ‘transcendentalizing’ it too far á la Husserl, and, on the other hand, that Arendt’s writings have a vast potential for contemporary social ontology, as pursued by phenomenologically oriented scholars.

In the third chapter of her book, Arendt’s Phenomenological Methodology, Loidolt focuses on two aims. First, she examines human conditionality, referring to a famous (and, as Loidolt shows, easy to misinterpret) systematization of activities from The Human Condition and emphasizing the enactive character of Arendtian conditions. Second, she develops an original interpretation of Arendt’s theory by applying the concept of ‘spaces of meaning’. The first subchapter criticizes approaches that tend to essentialize and solidify different activities and their respective conditions. These are often naively understood analogically to a baby shape sorter: just as every wooden block fits into a particular hole in a box, every human activity correlates to one of three categories. Loidolt, on the contrary, presents labor, work, and action as a dynamic structure, where all conditions are interconnected: “Since all conditions are actualized simply by human existence, i.e. by being a living body, by being involved in the world of objects/tools and by existing in the plural, being human means to dwell, however passively, in all of these meaning-spaces at one and the same time.” (116). In the second section, she presents what amounts to one of the most interesting moments of the book: the articulation of Arendt’s background methodology in terms of “dynamics of spaces of meaning” (123). According to this interpretation, every activity that takes place develops its particular logic, which can be described as a space of meaning. These spaces of meaning stand out as worlds with specific temporality, spatiality, a specific form of intersubjectivity, and an inner logic of sequence, rhythm, and modality (128). Loidolt adds a transformative dimension: a shift in meaning takes place when an activity and its space part (126). In this context, she takes up a controversial discussion about normative character of the private, the political, and the social space in Arendt and joins advocates of “an attitudinal rather than content-specific” interpretation of this distinction (145, cf. Benhabib 2003: 140). With her notion of meaning-spaces, Loidolt offers a vivid image that helps us to comprehend the structure of human existence as presented by Arendt in its full complexity. It also shows us how to avoid interpretative pitfalls resulting from attempts to essentialize human activities and ascribe them to a clear-cut realm, be it the private, the political or the social. Her main effort is directed towards emphasizing the activating element in Arendt’s account: the whole picture awakens before our very eyes.

Chapter 4, which opens the second part of Loidolt’s book, addresses plurality as political intersubjectivity. The author begins with an overview of different interpretations of plurality in various fields: political theory, social ontology, and in Arendt-scholarship. She presents a strong argument for political interpretation of plurality, which she describes as a plurality of first-person perspectives. Such a plurality forms a certain in-between, an assembly of those who act together, which provides a ground for any politics (153). When discussing plurality accounts within political theory (Mouffe, Laclau), Loidolt focuses primarily on post-foundational discourses and praises these for granting plurality ontological relevance. At the same time, she emphasizes that within this approach the first-person perspective gets lost. This, in turn, leads her to phenomenology. She positions her “phenomenological investigation into the social-ontological dimensions of plurality as a political phenomenon” (154) within the area of phenomenology, which addresses the “moral, normative and especially political dimensions of the ‘We’” (154, cf. Szanto& Moran 2016: 9). Subsequently, she sketches a broad context of Arendt-scholarship about plurality and draws our attention to the fact that a suitable answer to one fundamental question often remains a desideratum: What is plurality actually? (156) Loidolt develops an answer to this question in further sections of this chapter. She does so by, first, referring to Husserl and Heidegger – the move we already know from previous chapters. In what follows, she displays her phenomenological interpretation of plurality as ontologically relevant condition of beings as first-person perspectives, who exist in plural. As such, plurality has a fragile status: it can be actualized or not (175). This is one of the most philosophically dense parts of the book, where Loidolt formulates a number of illuminating theses to support her aim. She refers to well-known motives linked to plurality, such as uniqueness, the “who”, multiple points of view, web of relations, but she also evokes some new constellations, such as theorizing acting, speaking, and judging, as three equal-ranking modes of actualizing plurality (183). This chapter paves the way for the two that follow.

Chapter 5, “Actualizing a Plural ‘We’”, focuses on the question of actualization of plural uniqueness. Loidolt emphasizes the crucial problem of the fragility of plurality in terms of such an actualization: plurality can, but does not have to be, actualized. Arendt herself was aware of this fragility, not only in view of great catastrophes of the 20th Century, such as the rise of totalitarianism, but also in terms of human existence in a community in general. Plurality is the central condition of action, which facilitates an emergence of a public space. But ‘acting in concert’ – bringing multiple “who’s” into a common space of the political, is, as Arendt states, a rare event (Arendt 1998: 42). This might seem counterintuitive, since most of us are surrounded by other people on an everyday basis. But, for Arendt, not every human interaction is genuine action. To refer to a notion coined by Loidolt: the respective space of meaning must occur. According to the author, the three activities through which an actualization of plurality takes place are acting, speaking, and judging. As Loidolt herself admits, this constellation of activities is not a common move in interpretations of Arendt’s work (212). Indeed, Arendt counted judging among faculties of the mind. But to anyone familiar with Arendt’s work, Loidolt’s justification for bring the three together will be apparent. In the three sections of the chapter, she pursues a phenomenological inquiry of each of these activities with respect to their potential to actualize plurality. First, she brings Arendtian speaking together with Heidegger’s ‘being-as-speaking-with-one-another’ (195). She then presents acting as praxis or performance and points to its inherent connection to plurality: acting always appears within a web of relationships (200). Finally, Loidolt approaches judging not only in political terms, but she also draws our attention to its reflective dimension (213 – 218). However, judging differs from the other two activities because, while it seems capable of actualizing plurality as intersubjectivity, it does so in a slightly different space of meaning, which is not a space of appearance per se. Loidolt addresses the issue of public appearance directly in the course of this chapter, emphasizing that ‘actualized plurality needs the visibility of an in-between’ (225). The question of how this can refer to the faculty of judgment remains somewhat vague. It is clear that our “who” does not appear to others in judging in the same way, as it appears on what Arendt calls ‘the stage of the world’ (Arendt 2007: 233, 249. Arendt uses this expression only in the German version of the text). The community of judgment is an imaginary one, so we may only speak of appearance of the “who” in a metaphorical sense. Thus, Loidolt’s argument here calls for further investigation. This, however, does not jeopardize her overarching argument for an ethics of actualized plurality (230).

The question of normative potential of Arendt’s theory and its alleged ‘lack of moral foundations’ (233, cf. Benhabib 2006) is the theme of the last chapter of Loidolt’s book. As the author argues, a phenomenological inquiry shows that “ethical elements are inherent within Arendt’s conception of the political qua actualized plurality” (233) and do not need to be imposed on it from outside. The aim of this chapter is hence to provide the readers with an intrinsic ethics of actualized plurality (235). Loidolt begins with an analysis of thinking in Arendt. She does not follow interpretations “investigating the inner tension between the bipolar ‘moral self’ and Plurality”, but tends, rather, to maintain the specific separation of the political and the moral (234 – 235). This comes as a surprise, since Loidolt presents a convincing case for ‘pluralization’ of so many other phenomena throughout her book. Thinking, on the contrary, appears as a ‘solitary business’ and a ‘lonely experience’. This is a one-sided interpretation of Arendt’s concept of thinking. Obviously, it fits Loidolt’s argumentation at this point, but it also neglects the pluralistic aspect of thinking as an inner dialogue and its implications for the emergence of the ‘who’. As Arendt says, “And thought, in contradiction to contemplation with which it is all too frequently equated, is indeed an activity, and moreover, an activity that has certain moral results, namely that he who thinks constitutes himself into somebody, a person or a personality” (Arendt 2003: 105), even if she directly clarifies the difference between activity and acting. Loidolt takes a different path and describes thinking as a ‘derivative phenomenon’ (235) that cannot be a point of departure for an ethics of actualized plurality. Granted, this corresponds to the conditions of actualization of a “we”, which she identifies as: directedness/intentionality, authenticity, and visibility. At least visibility was not her concern in case of judging, though, while it seems to be decisive when it comes to denouncing thinking as a lonely enterprise. This, however, is my only criticism of Loidolt’s analysis. Overall, she presents a convincing account that integrates a particular normative – or rather proto-normative (234) – element into Arendt’s concept of plurality. She shows the fragility of the space created by action and plurality, but not only to emphasize its unsteady status. More importantly, she transforms this fragility into an asset: action follows its intrinsic logic, which means that it can be interrupted and taken up again, hence it is open to redefinition and reinterpretation by multiple interpreters (237). Through faculties of forgiving and promising, we establish relations between persons, which bring an element of the ‘empowerment through others’ into play (139). Loidolt then discusses ethical demands, which intertwine with domains other than the political: life, truth, and reason. Here, as she argues, actualized plurality is ethically relevant to addressing current global challenges of totalitarianism and biopolitics (234). Loidolt closes this illuminating chapter by reaching out to Lévinas and his ethics of alteritas and by presenting benefits of interrelating both theories (252).

Loidolt rightly contests the common belief that Arendt’s methodology was eclectic and random (52). Through her thorough and deep phenomenological investigation of Arendt’s political thought, she makes a successful attempt to display its overall methodological framework (which may not even have been fully evident to Arendt herself, considering her lack of interest in a methodological self-analysis). Husserl and Heidegger play a major role as references in Loidolt’s study, which is methodologically and historically comprehensible. It is an additional benefit of the book that she brings other phenomenologists from the ‘second generation’ (7) into play, which further underlines the potential for Arendt’s work to guide contemporary phenomenological inquiry. Loidolt also draws our attention to a particular feature of Arendt’s corpus: she wrote many of her texts first in English – a foreign language to her and not the one in which she received her philosophical education – then rewrote them in German herself. (12, 265). Loidolt, a native German speaker, observes that she found phenomenological traits to be omnipresent in the German versions of Arendt texts. She was surprised to discover that these traits were either much less apparent orabsent entirely from the English versions. This, I would argue, is one of the reasons why Arendt’s potential for phenomenology is not universally recognized and also why phenomenological takes on Arendt remain outside of the mainstream of Arendt scholarship, at least within the Anglophone reception. Another reason lies probably in the difficulty involved in comprehending Arendt’s particular phenomenological approach. However, Loidolt suggests that doing so is the only way to fully understand Arendt. I am not convinced that this claim can be supported without restrictions. First, there are multiple very appealing interpretations of Arendt that completely abstract from her bonds to phenomenology. Second, it seems to be quite far away from the Arendtian spirit to assert that there is only one perspective on a story. Loidolt herself emphasizes that she does not want to force Arendt into any club (2). Nevertheless, through her impressive study, Loidolt advocates her case very convincingly. It is possible to see Arendt’s work through multiple lenses, but it is indeed very difficult to ignore the phenomenological lens, since once it has been applied what has been seen cannot be unseen. Therefore, due to its comprehensiveness and the depth of Loidolt’s analysis, the book has great potential, not only to inspire a new, phenomenologically-oriented appreciation of Arendt’s work but also to become a crucial contribution to Arendt scholarship.

References

Arendt, Hannah. 2007. Vita activa. München/Zürich: Piper.

Arendt, Hannah. 2003. Some Questions of Moral Philosophy. In: H. Arendt, Responsibility and Judgment. New York: Schocken.

Arendt, Hannah. 1998. The Human Condition. Chicago: Chicago University Press.

Benhabib, Seyla. 2006. Judgment and the Moral Foundations of Politics in Arendt’s Thought. In: Garrath Williams (ed.), Hannah Arendt: Critical Assesment of Leading Political Philosophers, Vol 4., pp. 234 – 253. London/New York: Routledge.

Benhabib, Seyla. 2003. The Reluctant Modernism of Hannah Arendt. New Edition. New York: Rowman & Littlefield.

Szanto, Thomas & Moran, Dermot (eds.). 2016. The Phenomenology of Sociality: Discovering the ‘We’. London/New York.

Young-Bruehl, Elisabeth. 1982. For Love of the World. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Feminist Phenomenology Futures

Feminist Phenomenology Futures

Reviewed by: María Jimena Clavel Vázquez (St. Andrews/Stirling Philosophy Graduate Programme)

In Feminist Phenomenology Futures we find a multiplicity of approaches, experiences, and points of view of intellectuals working on feminist phenomenology. But, which is the guiding thread that unites them all? On the one hand, we may say that this is a book about current approaches to feminist phenomenology united solely by that, by providing accounts that fit into the framework of this discipline. And, although the multiplicity of points of view is central not only to this book but to this endeavour, we need to focus on something else. What matters is not only the currency of these approaches, but the future that is latent in them. This, of course, is made explicit in the title of the compilation. However, this might be difficult to grasp. So, I believe it is worth pausing here to clarify exactly what this means because this is not only the most relevant feature of this compilation, but its greater contribution.

As I said, this book is concerned with the future of feminist phenomenology. At this point we should note that we are not asking for the expected outcome of a research programme and the methodology that will lead us to it. It is neither a book that seeks to unify a discipline and mark the path for its future development. This book is, rather, traversed by a question regarding the destiny of feminist phenomenology. Or, in other words, feminist phenomenology considered as a project. The future, in this context, is not something that belongs to a chain of events, nor an “empty zone”, as Dorothea E. Olkowski and Helen A. Fielding state in the introduction. It is rather the future of experience. In her article “Open Future, Regaining Possibility”, to which I will later return, Fielding claims that our experience is characterised by simultaneity in that it is a “gathering of the past and future in the present experienced from a point of view by someone who perceives, feels, thinks, and acts” (94). The future is already sketched in us, embodied and situated beings. This allows us to comprehend the relevance of populating feminist phenomenology with multiple voices. As Fielding emphasizes at the beginning, in “A Feminist Phenomenology Manifesto”, the future in this context should not be understood as a unifying force, but as the opening of possibilities in our experiences and these, we must add, are never uniform but multiple. The future belongs to this discipline because it recognizes such multiplicity. In this manifesto, Fielding claims that at the core of feminist phenomenology is a “decentered subject” that is “multiple rather than singular” (viii). Feminist phenomenology becomes, thus, the methodology of the future because it emphasizes as its guiding task the opening of possibilities. In this line, Fielding claims that at the core of this understanding of feminist phenomenology lies “the recognition that there are multiple ways of approaching living experience” (vii). Furthermore, there lies a compromise of accounting for the experiences of embodied and situated agents and their worlds: “we need robust accounts of embodied subjects that are interrelated within the world or worlds they inhabit” (viii). This compromise is what turns feminist phenomenology into an emancipatory endeavour.

Part 1. The Future Is Now

As Olkowski and Fielding notice in the introduction (pxxiii – xxiv), the phrase “the future is now” is commonly used but hardly explained. So, how are they interpreting this phrase? The authors draw on Merleau-Ponty’s interpretation of Feuerbach. According to Merleau-Ponty, Feuerbach is claiming that being should not be taken to be an abstraction, but as something embodied, involved in the senses, attached to life. Philosophy thus becomes a new happiness, the joyful expectation of a project to come that involves us all, embracing the forces traversing our current experiences. The future in this sense is the future that is sketched in us. The papers in this section address this outline, that is, the future as it appears in us.

The paper that inaugurates this section is Dorothea E. Olkowski’s “Using Our Intuition: Creating the Future Phenomenological Plane of Thought”. Throughout this paper, she advances the thesis that intuition should be considered the structure for the methodology of feminist phenomenology. Olkowski starts from the situated woman, someone whose situation is identified with her body, and which is shaped by culture, history, and society. In that sense, her being is temporal. However, Olkowski sees a problem in the way her body has been considered because instead of being recognized as “her freedom, her transcendence”, she has been taken to be “embedded in her embodiment” (4). This is what Olkowski wishes to challenge: the idea that feminist phenomenology is particularly concerned with embodiment because the body represents the opposition to traditional notions of reason and knowledge. The problem, then, is that this notion became more relevant in the context of feminist phenomenology than in other areas of philosophy. In order to tackle this issue, Olkowski explores the plane of thought that underlies this phenomenon, that is, its “milieu of concepts and methods” (6).

Olkowski defends, drawing on Merleau-Ponty, de Beauvoir, and Bergson, that the plane of thought that is adequate to account for embodiment, without stripping it away from the freedom that constitutes it, is the vital form or the plane of the virtual which brings together the realm of language with that of nature (10). Between language and nature lies a structure of significance where the perceptible acquires meaning. Consciousness is not apart from the body, rather in the present, consciousness exists as the body where past and future meet (12). It is in the temporal structure of the embodiment that intuition can be considered once again as the structure that guarantees that action is creative instead of being just a repetition of previous patterns (13).

In “Just Throw Like a Bleeding Philosopher: Menstrual Pauses and Poses, Betwixt Hypatia and Bhubaneswari, Half Visible, Almost Illegible”, Kyoo Lee is concerned with the way feminist phenomenology can face the complexity of embodiment (25). In particular, she is interested in an analysis of menstruation. To do so, she focuses on the double structure that constitutes menstruation: “The menstruator enters and exits the cycle of life simultaneously while bleeding herself into a revolving door she herself becomes, beginning to exist and exit at once in syncopation that seems to have a will, a script, of its own” (30). On the one hand, it is an overcharged phenomenon that marks the entrance of women into existence; while, on the other, it is an overlooked phenomenon in that it hides women in plain sight.

Lee puts forward two cases where this phenomenon is brought into view. Firstly, the case of Hypatia: when a student declared his love to her, she threw her menstrual handkerchief to his face, to show that she who was the object of his Platonic love was also this embodied being. This way, she was not only affirming herself as female, but also bringing to light this double structure. Lee claims that she is throwing it “back at the smug face of philosophy that says one thing and does another or the other” (p. 34). Lee also goes through the case of Bhubaneswari Bahduri, a young woman from North Calcutta sixteen or seventeen years old, who committed suicide specifically on the time of her menstruation. Bhubaneswari had joined a terrorist group but then escaped the entrusted task of assassinating a political figure through her suicide (p. 37). Her action challenges the “patriarchal violence, the class system, and the colonial rule” (p. 38) precisely because every single one of her actions was a liberating act. Both Hypatia and Bhubaneswari throw back the situation to which they are thrown to, opening in this way alternative futures for women.

The third paper in this section is “Transformative Lines of Flight: From Deleuze to Masoch” by Lyat Friedman. Drawing on a text by Deleuze and Guattari called Kafka: Toward a Minor Literature, Friedman seeks to disentangle the opposition men-women by providing a “line of flight” or a way out. For her, this method offers alternative interpretations that do not contest an opposition, rather they complicate it (49). Friedman starts by providing an account of the opposition men-women. Following de Beauvoir, she argues that this opposition does not resemble that of two opposing poles. While women are the negative, the Other, men are not only the positive but the neutral as well.

Friedman draws on Deleuze’s interpretation of Sade and Masoch, and the women from their texts. As de Beauvoir notes, one of the features of these texts is that they present the male perspective of different types of women (56). Sade depicts his male protagonists as figures of power whose opposite is a victim or prey. Masoch, on the other hand, offers a male protagonist who thrives on humiliation. His opposite is a woman who “refuses to act from her position of power” (56). As Friedman notes, these structures are incompatible. The author finally returns to de Beauvoir’s position as it appears in an article called “Must We Burn Sade?” There de Beauvoir intends to provide a charitable understanding of Sade’s expression of hatred towards women, offering thus an interpretation of his texts that breaks with binary oppositions. She claims that: “We must learn to avoid reiterating oppositions even as we disagree with them. We must find lines of flight, identify intersections, and leave given paths, if only to produce alternative futures for women and men” (62).

The last paper of this section, “Crafting Contingency” by Rachel McCann, offers an exploration into the creation of alternative social paths. For McCann, architectural design provides, firstly, a field for understanding the complex interactions between a system and its environment, the organisation of a system that reiterates a pattern, and the way this pattern transforms and transmits information. For her, patterns are reiterative, complex, and, at times, flexible structures. The exploration of these concepts allows her to posit a model for effecting social change. Drawing on bell hooks, McCann claims that “in order to effect social change we must position ourselves at once on society’s margins and at its center” (73). Social change will come from creatively reconfiguring the boundaries that cannot be crossed. Effecting change in these structures will lead to an eventual restructuring of the world (81).

Part 2. Negotiating Futures

A different notion of future is at play in the second section. In the introduction (xxv-xxvi), Olkowski and Fielding note that the opening of emancipatory possibilities requires the commitment of bringing about these projects. Ultimately, it requires erasing the boundaries between reason and passion: these emancipatory possibilities are not only sketched in us, but they are also something that is affirmed through passionate action. Bringing about these possibilities involves audacity in that there is always a risk of failure. Now, this notion of project has a retrospective character because the future is not something that breaks with the past, that is, built from scratch. As Olkowski and Fielding note, when others look back into these projects the future appears not as a possibility but as something that was inevitable, something that was bound to happen (xxvi).

The first paper in this section, “Open Future, Regaining Possibility” by Helen A. Fielding explores situations where personal time, that is, time as it appears in our experience, breaks down. To do so, she draws on Merleau-Ponty’s distinction between impersonal time, personal time, and objective time. Fielding describes personal time in terms of simultaneity. As mentioned earlier, she considers this to be a gathering of present, past, and future (94). Fielding describes temporal break down as the closure of possibilities, as the loss of “the phenomenal experience whereby each moment is full of the living possibilities with which we ‘reckon,’ possibilities that are actualized as possibilities…” (95). She explores this phenomenon in light of a couple of cases in which online bullying resulted in the suicide of its victims. In these cases, Fielding argues, these teenagers suffered from a depression that involved the break down of personal time. An important factor in these cases is the temporality that is involved online: “on the internet temporality is collapsed into space” (96).

In the second paper of this section, “Of Women and Slaves”, Debra Bergoffen discusses de Beauvoir’s notion of an original Mitsein. Bergoffen starts from the idea that de Beauvoir’s position allows a movement from women considered as an oppressed Other to the “dignity of difference” (110). De Beauvoir is troubled by the fact that, despite being oppressed, women do not rebel. Bergoffen explains that for the French philosopher this is rooted in an original bond between men and women: an original Mitsein. Rebellion makes sense when the other is not absolute but relative, but this is not the case of women for de Beauvoir. For this reason, Bergoffen develops an exploration into de Beauvoir’s original Mitsein. For her, this concept “identifies the couple as the site where… desire is fulfilled” (115). Unlike slavery, oppression in the case of women does not aim towards destruction but domestication. The author explores this notion in connection with de Beauvoir’s claim that women are slaves to their husbands. Furthermore, she offers an analysis that takes into account the intersectionality of subjects, the crossroads between race and gender, and the vulnerability of women who are not privileged.

In the final article of this section, “Unhappy Speech and Hearing Well. Contributions of Feminist Speech Act Theory to Feminist Phenomenology”, Beata Stawarska addresses the phenomenon of speaking as a woman. Drawing on Austin’s theory on language performativity, she proposes to think of the failure of woman being heard as a failure in the illocutionary force of the speech. According to Stawarska, when a speech is performed by a socially dominant speaker, it enjoys a force that gets lost when it is spoken by a non-dominant speaker. For her, this failure is one that is socially modulated. To address this phenomenon, she complements Austin’s theory with a phenomenological perspective. The gender-power imbalance results in an infelicitous enactment of a speech act. Stawarska shows that the success or failure of a speech act depends not only on the speaker, but on the listener as well: “The hearer’s uptake is both the effect of what is being said and the condition of the saying acquiring the force of a speech act” (132). Addressing the silencing of women requires, then, to cultivate not only the speakers but, importantly, the listeners: it is essential to cultivate an attentive listener.

Part 3. The Ontological Future

In the third section of this compilation, the authors offer an ontological perspective on the future as it appears in experience. Olkowski and Fielding draw on Husserl’s notion of internal temporality (xxvii). For him, what appears to consciousness does so in continuing phases and enjoys a unity that is synthetic: this flowing away belongs to the way objects appear to consciousness. In other words, the objects of consciousness get their unity and identity from this “flowing subjective process” (xxvii). Taking this into account is essential for the task of feminist phenomenology as an ontological endeavour. The authors complement Husserl’s take on internal time with Henri Bergson’s ontological memory: “even our most minute sensations form an ontological memory, images created by the imperceptible influences of states in the world on our sensibility” (xxvii). In this sense, in experience our present coexists and interacts with the past: new experiences alter the past and create new possibilities. For the authors, this is essential to understand that we are projected beings.

The first paper in this section, “Adventures in the Hyperdialectic” by Eva-Maria Simms, develops Merleau-Ponty’s method of the hyperdialectic. To do so, Simms starts by exploring Merleau-Ponty’s notion of the gestalt principle. For Merleau-Ponty, a gestalt is a consideration of a new dimension of order. This refers to “a system that is more than the sum of its parts” (144) and that stands as the transcendental field of the objects that appear to consciousness. According to Simms, the hyperdialectic is a method that allows the formulation of a set of principles that accounts for being understood not as an absolute, but as a gestalt. In this sense, Merleau-Ponty’s hyperdialectic opposes the dialectic method that loses touch with the concrete (143). Simms is interested in providing an account of gender through the method of the hyperdialectic. At the end of this paper, she provides a short outline of this account.

In “The Murmuration of Birds. An Anishinaabe Ontology of Mnidoo-Worlding” by Dolleen Tisawii’ashii Manning, the author advances an outline of the ontology of the Algonquian language family from North America. She is particularly interested in the notion of mnidoo, a concept that among other things, means spirit, substance, nature, essence, mystery, potential. Manning is interested in showing that mnidoo-worlding, that is, mnidoo dwelling in the world is an unconscious “conceding” that is “embedded over generations” (156). To explore this ontology, the author draws on the phenomenology of Husserl and Merleau-Ponty, particularly on the latter’s notion of chiasm. Manning advances a notion of consciousness that surpasses animal or human sentience and locates in the world (p.162). This opens a dimension or center that connects and goes through the bodies (animate and inanimate) that constitute this center. This entails that, in mnidoo-worlding, these bodies fuse to become an indistinguishable whole. The relation between the bodies that constitute the whole is, for her, “an ownmost immediate knowing”, a familiarity that exceeds the subjective: “Nii kina ganaa – All my relations/All my relatives/My all/My everything” (165).

Christine Daigle’s “Trans-Subjectivity/Trans-Objectivity” is situated within the framework of the ethics of flourishing. Discussing with (and drawing on) several philosophers, such as Nietzsche, Deleuze, Heidegger, and Foucault, she wishes to provide an account of the human being as trans-subjective and trans-objective. Hers is a weak ontology in that it provides a deep reconsideration of the relation between human beings and their worlds. Daigle begins with the idea that our body is the anchor to the world. However, the boundaries of the body are not fixated, rather they are on the making. Not only that, for her, human beings are transformed in their engagements not only with others but with the world as well. These transformations have an ontological dimension: they transform our being. Daigle uses the trans((subj)(obj))ective structure to account for trauma and its everlasting effects. She claims that: “What a trans((subj)(obj))ective being does to another is not circumscribed in time and space, but it is an everlasting deed. It is constitutive of one’s being as both trans-subjective and trans-objective…” (195).

Part 4. Our Future Body Images

As mentioned earlier, the future is already sketched in us and part of that outline is our body image. As Olkowski and Fielding state in the introduction: “The body image is a vital prereflective sketch of the body’s practical possibilities for engagement with the world” (xxix). This turns out to be essential to the understanding of an agent. The authors draw on Gail Weiss’ notion of the body image, which claims that this is “an active agency that has its own memory, habits, and horizons of significance” (Weiss, Body Images, p. 3, as it appears in p. xxix). The texts in this section reflect precisely on the idea that the body image is our embodied experience in the world, an image that makes sense in the intertwining of our interactions with the world and with other agents, and that emerges from these interactions. The body image in that sense is both individual and social. It is individual in that it tracks my specific engagements and point of view. However, it also tracks the norms and the structures of our interactions with others, our social practices. Paying attention to our image is essential to the project of feminist phenomenology and its emancipatory character. As Olkowski and Fielding claim: “Since corporeal schemas reflect the ways we take up the world, shifting these practical possibilities or embodied norms is pivotal to shifting practical possibilities, and, similarly, bringing concrete change to our world can also shift the ways we move and hence our bodily schemas” (xxix).

Gail Weiss, in the paper “The ‘Normal Abnormalities’ of Disability and Aging. Merleau-Ponty and Beauvoir”, addresses the ambivalent attitudes towards people who do not conform to the normative standards of beauty in a society. Weiss follows Julia Kristeva in claiming that human beings avoid confronting their vulnerabilities by projecting onto others “the status of abject other” (204). The author claims that avoiding someone with what she calls a non-normative body is a strategy to avoid thinking about our own possibilities. Weiss emphasizes the paradox of the abnormalcy of age. Although it is considered non-normative, or an abnormal body, the thing is that we will all age. In consequence, Weiss argues, it is impossible to distance ourselves fully from this image.The author explores de Beauvoir’s perspective on this phenomenon. Weiss argues that ageing involves an alienating experience. The problem is that vilifying ageing “is clearly against the self-interest of each of us to the extent that we aspire to live a long life” (209). To explore the phenomenon of disability, Weiss draws on Merleau-Ponty. Merleau-Ponty argues that this phenomenon allows us to understand better our perceptual engagements. Weiss takes Merleau-Ponty’s discussion about the Alzheimer patient who, despite her cognitive impairments, inhabits her world meaningfully. For Weiss, it is Merleau-Ponty’s position that allows the normalisation of the abnormal (212) and, in consequence, it allows us to challenge the oppressive considerations of the non-normal body.

The next paper, “The Transhuman Paradigm and the Meaning of Life” by Christina Schües addresses the way biotechnology impacts our experiences and, in consequence, the meaning of life. Bio-phenomenology is able to provide an account of the way meaning is transformed through the introduction of new technologies and its intertwining in our biographies. She claims that: “Bio-phenomenology provides an appropriate approach to investigating the underlying dimensions of meaning and the structures of experiences, which concern the biotechnological, medical, and reprogenetic practices in the transhuman paradigm” (225).

In “The Second-Person Perspective in Narrative Phenomenology” Aneemie Halsema and Jenny Slatman offer a phenomenological consideration of the second-person perspective and its relevance in sense-making. They focus specifically in research interviewing in cases of breast cancer diagnosis. The authors explore the role of the interviewer in the way the respondent articulates her experience. For them: “Sense-making is not the work of an individual, but takes place in joint narrative work” (243). They show that language co-creates experiences drawing on the work of Paul Ricoeur.

In the final paper of this section, “Hannah Arendt and Pregnancy in the Public Sphere”, Katy Fulfer challenges Arendt’s idea that pregnancy cannot be considered a public activity. Interestingly, she does so from Arendt’s own distinction between the private, the social, and the public. Fulfer is specifically concerned with issues regarding reproductive justice in cases of contract pregnancy. Fulfer argues that Arendt’s notion of the social allows her to show that pregnancy surpasses the private realm. The social realm is defined as that in which the necessities of life take the place of the public or the political. This is the case of contract pregnancy when considered as a biopolitical phenomenon. Fulfer defines the biopolitics as that which “offers governing bodies the ability to control bodies and populations under the guise of promoting the health of individuals” (260). Given that gestational workers are controlled and disciplined through contracts and political rhetoric, Fulfer claims that they are no longer considered as political agents but as workers whose job is to preserve a life, entering thus the social realm. The author argues as well that there is also an aspect in which gestational workers enter the public realm through political discourse, a discourse that takes place when they discuss their own situation, and that in some case impacts their contracts.

Part 5. Present and Future Selves

In the final section of this compilation, we find papers that address the world as it has been configured by the actions and speeches of “our past selves”, as Olkowski and Fielding advance in the introduction (xxxi). These papers scrutinize and evaluate the possibilities that were configurated before us. This is the retrospective character of the future that was mentioned in part 2.

The first paper of this section, “Is Direct Perception Arrogant Perception? Toward a Critical, Playful Intercorporeity” by April N. Flakne argues against analogical theories of the perception of others. For her, these theories eliminate difference, something that is essential in our considerations of the other, by modelling the other “on oneself” (278). To make her case, Flakne joins the defenders of direct perception, a theory according to which our perception of others is not mediated by either a theory of the mind of others or by a re-enactment of others’ mental states (i.e. the simulation theory). The idea behind direct perception is that we encounter others “because they comport themselves toward the world” (281).

Flakne argues that in order to avoid arguments that model the other after oneself, it is necessary to focus on the spaces where the other demands a response or an interaction: “an occasion for uptake and response that we cannot present ourselves” (289). The author draws on Maria Lugones who claims that individuals are not discrete, rather they are constructed by a world that is shared. She takes Lugones’ notion of world-travelling according to which we approach the other by being affected by other worlds. Our identity is, for Flakne, constituted by the playful corporeal interaction with others. Through the notion of this playful interaction, Flakne wishes to give new directions to direct perception.

“Leadership in the World Through an Arendtian Lens” by Rita A. Gardiner challenges contemporary accounts of authentic leadership, an enquiry that began as an ethical evaluation of leadership positions and practices, and that evolved into a prescriptive discipline that accounts for the features a leader should have. The problem of these accounts is that, from a phenomenological perspective they fail to account for lived experience. Furthermore, they equate authentic leadership with moral goodness (302). Drawing on Arendt, Gardiner wishes to advance a notion of leadership that emphasizes collaboration as an essential element of leadership. She claims that “freedom and power are impossible without the ability to act in concert with others” (304).