Kierkegaardian Phenomenologies

Kierkegaardian Phenomenologies

New Kierkegaard Research

Lexington Books

2024

Hardback $115.00

Kierkegaardian Phenomenologies

Kierkegaardian Phenomenologies

Event and Subjectivity: The Question of Phenomenology in Claude Romano and Jean-Luc Marion

Event and Subjectivity: The Question of Phenomenology in Claude Romano and Jean-Luc Marion

The “aging” of Adorno’s Aesthetic Theory. Fifty Years Later

The “aging” of Adorno’s Aesthetic Theory. Fifty Years Later

Reviewed by: Anna Angelica Ainio (PhD ETH Zürich)

The idea of aging seems, at first sight, to be at odds with the concept of theory itself. Theory is supposedly something immaterial that should encompass or anticipate the idea of a development with time, or at least this would be the case if we were talking about theory in the context of systematic or analytic philosophy. Instead, the concept of aging (Altern) in Adorno’s theory is at centre of a discourse tied to his conception of history with regards to critique. The very idea of critical theory, as the first generation of Frankfurt School intellectuals posited it, is a movement which intervenes on concepts, such as that of truth, that are to be understood historically. This entails that the question of aging assumes specific historical connotations and becomes an essential element in the process of criticism. Indeed, it is only because of its temporal core that a theory can become dialectical and therefore gain historical consistency for Theodor W. Adorno.

However, another question which might come to mind when thinking about aging is in which way the type of aesthetic theory that Adorno delineated would still have to do with today’s artistic development. It is through these lenses that the book, ‘The Aging of Adorno’s Aesthetic Theory’, edited by Samir Gandesha, Joan Hartle and Stefano Marino, looks at Adorno’s aesthetics and gives a nuanced and multifaceted account of it. The book, which was published in 2021 by Mimesis International, presents fourteen critical essays by international scholars and an editorial introduction.

The editors choose to utilize the concept of aging, as explicated in the title, as they deem it to be central to the Adornian conception of criticism (Gandesha S., et al., 9). Indeed, aging is delineated as a dialectical quest for what remains of the philosopher’s aesthetics, conveyed through different writings among which his last and perhaps most enigmatic work: Aesthetic Theory (Ibidem, 11). As an unfinished manuscript, Adorno’s work has received renewed critical attention from the eighties onwards. In ‘The “Aging” of Adorno’s Aesthetic Theory’, the authors frame their and their contributors’ approaches as a critical dialogue with Adorno. The multiplicity of texts that they include, as they put it, ‘often proceed dialectically “with Adorno” and simultaneously “against Adorno”’ in a productive dialogue that aligns with Adorno’s own understanding of a critical philosophical dialogue, as he himself outlines it with regards to Hegel (25). Indeed, this type of approach considers how one can productively engage with Adorno’s aesthetic theory today by following the pathway of the Adorno’s own approach to Hegel – that is, thinking about what Hegel himself would have said with regards to the present (24). That means engaging in a critical understanding of the philosopher that neither is a defense nor is it an ‘exercise of distinguishing between “what is living and what is dead”’ (ibidem).

An instance of this re-evaluation from within Adorno’s theory is Gunter Figal’s essay ‘Is Art Dialectical? Adorno’s Aesthetic Theory Revisited’, where the author argues that one should critically assess the fact that, for Adorno, art ought to be necessary dialectical. Through a thorough analysis of Adorno’s aesthetics which goes back to its Hegelian and Kantian roots, Figal sustains that there is a need to overcome Adorno’s dialectical understanding of art as it is bound to the idea of ‘artistic rationality’ (87). Indeed, to build a dialectical understanding of art, Adorno needs to posit the existence of an artistic rationality which would resemble the determined rationality Adorno identifies to be constitutive of contemporary society. However, this is at odds with some instances of contemporary artistic endeavours where the creative act does not embrace the sort of all-encompassing controlling rationality that characterizes society, as Adorno describes it. Figal gives the example of Jackson Pollock’s dripping technique, where the element of chance is incorporated in the act of artistic creation (90). Figal’s is a provocative take on aesthetic theory, and one that wants to provoke discussion within the scholarly community.

Gerhard Schweppenhäuser’s essay, titled ‘Nature and Society in Adorno’s Aesthetic Theory’ cleverly considers the role played by natural beauty and its nuanced conception in Adorno’s aesthetics. Indeed, because the concept of natural beauty is at the basis of Adorno’s utopian conception of art, Schweppenhäuser tries to outline how this plays a part when one wants to consider the philosopher’s aesthetic theory together with his theory of society (105). Indeed, Adorno’s aesthetics and social philosophy inform one another as artworks ‘stand for the right of the suppressed nature to exist’ (96). Therefore, as the concept of natural beauty has become absurd in a reified society, the very utopian moment resides in the artworks that structurally aim towards this conception. At last, Schweppenhäuser quite on point emphasizes the reflective moment in Adorno as the kernel of both his theory of society and of art. Therefore, what is rendered visible in Adorno’s conception of art is its reflective character which lies bare art’s inherent contradictions (110-111). This in turn reflects the social sphere as art is a ‘fait sociale’ and becomes the ultimate source of criticism (105).

Another significant contribution on the topic of the formal structure of artworks is that of Giacchetti Ludovisi. In his essay ‘Aesthetic Form and Subjectivity in Adorno’, Ludovisi shifts from a viewpoint that necessarily wants to evaluate Adorno’s conception of autonomous art in contrast to non-autonomous art and argues that one productive way to look at Adorno’s aesthetics is by linking the formal structure of art to psychoanalytical interpretation. Ludovisi creatively draws parallelisms between psychoanalytical concepts and formal structures of art situating his essay within interpretations such as Joel Whitebook or Amy Allen’s (Whitebook 1996; Allen 2020). Moreover, Ludovisi productively emphasizes the formal aspects of Adorno’s artistic criticism drawing on Adorno’s own work as a composer within the context of atonal music.

The book is composed of five different sections, each of which collects two to three essays from international Adorno scholars. Each one of the different parts is thematic and aims at dealing with a specific aspect of today’s scholarly debate on Aesthetic Theory. The sections are titled Revisions, Conditions, Materiality, Constellations and Contemporaneity. While the division of the book into different parts presents a useful tool for navigating its structure, it may feel arbitrary at times. An instance of this are section two, ‘Conditions: On the (im)pulse of Adorno’s Aesthetic Theory’ and three ‘Materiality: on the construction of the specific in Adorno’s Aesthetic Theory’, where the dividing line between the two is blurred at times. Hence, an essay such as Surti Singh’s ‘Adorno’s Aesthetic Theory: the artwork as a monad’ could have easily been placed in the second section, as it deals with the interpretation of Adorno’s aesthetic theory considering the Leibnizian conception of monads.

Moreover, while the book achieves its aim in giving a nuanced account of Adorno’s Aesthetic Theory fifty years after its publication, the choice of including such a wide number of essays risks losing the common thread which ties them all together. Despite this lack of a unitary point of view, which might impact the reader which approaches this collection from beginning to end, the book’s eclectic character can be one of its strong points too. A prismatic collection of viewpoints on allegedly one of the thorniest parts of Adorno’s theory, this book represents a refreshing collection of original contributions, each one to be extracted and read singularly. Moreover, an excellent introduction by the three editors sets the tone of the book and signals that there is a harmonized critical approach from authors that have indeed collaborated in the past. The choice of essays present in the book shows the originality of the editors’ perspective on contemporary Adornian scholarship and makes the book a precious collection of scholarly essays.

References:

Gandesha, S., et al. 2021. The “aging” of Adorno’s Aesthetic theory. Fifty Years Later. Milan: Mimesis International.

Whitebook, J. 1996. Perversion and Utopia: A Study in Psychoanalysis and Critical Theory. Cambridge. Mass: MIT Press.

Allen, Amy. 2020. Critique on the Couch: Why Critical Theory Needs Psychoanalysis. Vol. 73. New York: Columbia University Press.

Kant and the Phenomenological Tradition | Kant und die phänomenologische Tradition

Kant and the Phenomenological Tradition | Kant und die phänomenologische Tradition

The Palgrave Handbook of German Idealism and Phenomenology

The Palgrave Handbook of German Idealism and Phenomenology

Reviewed by: Luz Ascárate (University Paris 1 Panthéon-Sorbonne)

In response of the increasingly overwhelming interest of today’s scholars in various forms of naturalism and realism, Cynthia D. Coe offers us a look at the opposite side of philosophy, that inhabited by German idealism and phenomenology. Theses traditions, as the editor states, “jointly provide a counterpoint to the veneration of a materialist worldview and empirical methods of investigating reality that have dominated not only the natural and social sciences but also analytic philosophy” (p. 1). We believe that it is important to make this counterpart since, in the face of these tendencies, the Husserlian phenomenological project of saving man from being treated as a fact (Husserl, 1979) cannot be more relevant today: there are indeed still reasons to defend human freedom in terms of an irreducibility of the humanity or the spirit to the material conditions of scientific and technological progress. Unfortunately, the defence of this irreducibility in both German idealism and phenomenology have been widely misunderstood, in the sense that these traditions are accused of flat intellectualism and forgetfulness of reality, to say nothing about the supposed obscurity of the language and theories of their exponents, who have certainly preferred theoretical rigour to clearness of expression.

Now, with respect to the links immanent to the development of the studies of these traditions, much has been said about the influence of thinkers such as Kant, Hegel, Schelling or Fichte on the phenomenological proposals of Husserl (Steinbock, 2017, chapter 4), Heidegger (Slama, 2021), Fink (Lazzari, 2009) or Merleau-Ponty (Matherne, 2016), among others. However, this collective work offers us a vision of phenomenology either as a reappropriation, overcoming or continuation of the project of German idealism. Therein lies its importance. According to Cynthia D. Coe there would thus be a continuity to be emphasised between the preoccupation with consciousness in German idealism and the phenomenological preoccupation with first-person lived experience. This continuity is reviewed by the contributors to this book on different thematic fronts which articulate the 6 parts of this book: subjectivity, intersubjectivity and the other, ethics and aesthetics, time and history, ontology and epistemology, hermeneutics.

Throughout the contributions in these parts, we can identify the influence of German idealist thinkers on Husserl and on the phenomenological tradition in general. In addition, some contributors choose to point out the problems of interpretation of either Husserl or other phenomenologists with respect to the most representative texts of German idealism. In other contributions, the influence of the German idealist project on the conception of the phenomenological project can be seen. Finally, it can also be observed that the very definition of phenomenology for some representatives of this movement owes as much to Husserl as to German idealism. There remains, however, an interpretative line to be explored: in what sense phenomenology has been important not only for the reception of German idealism, but also for current studies of this tradition, contributing themes, angles, or interpretative nuances that the specialists of German idealist thinkers may not follow, but with which they discusse and dialogue. Although the importance of phenomenology for current studies in German idealism is a fact that we can ascertain (see for exemple Schnell, 2009), no author of this book cares to make this explicit. The directionality that the dialogue between these traditions thus takes is to start from German idealism to see its influence on phenomenology and to return to German idealism only if there is an error of interpretation to be criticised with respect to a specific problem. But let’s take a closer look at the content of the contributions in this book.

We would say that the concern with the concept of subjectivity can itself characterise both the idealist tradition and the phenomenological tradition. The contributions in the first part of this book are devoted to this common concern. Dermot Moran, in his paper entitled “Husserl’s Idealism Revisited” (pp. 15-40), drawing on Husserl’s understanding of the intentionality of consciousness, reveals that the place given to consciousness leads him to affirm a new kind of transcendental idealism. Husserl’s idealism, akin but not comparable to that of German idealism, gives intersubjectivity a fundamental character. But if Moran focuses exclusively on Husserl’s thought, the two following contributions in this part explore more closely the relationship between Husserlian phenomenology and German idealism.

Claudia Serban’s contribution (pp. 41-62) discusses the relation between the transcendental I and empirical subjectivity in both Kant and Husserl, differentiating their conceptions. The transcendental perspective is positioned here, in both authors, against the psychological and anthropological perspective regarding the concept of the inner man. First of all, the author opposes Husserl’s and Kant’s perspectives on internal and external experience within the horizon of the purely psychological perspective. Serban insists on defending Kant against some of Husserl’s criticisms. This opens the way to the Kantian distinction between the inner man and the outter man that appears in the context of his anthropology. Anthropology will try to be brought closer, by Husserl, to transcendental phenomenology. The paper thus shows how Husserl and Kant converge in the continuation of the transcendental perspective in an anthropology.

Federico Ferraguto, in his chapter (pp. 63-83), explores the relationship between Fichte and Husserl. Ferraguto begins with a reconstruction of Fichte’s influence on Husserl, and then points out the role of the self in the constitution of knowledge and thus in the conception of philosophy as a rigorous science for both authors. While it is clear that subjectivity is a fundamental theme of Husserlian thought, it is also present in other representatives of phenomenology. In this sense, even with regard to subjectivity, the last two contributions of this part follow closely the relationship between Gabriel Marcel, Jean-Paul Sartre and German idealism.

The article “Bodies, Authenticity, and Marcelian Problematicity” (pp. 85-106) by Jill Hernandez explores the influence of German idealism on Marcel’s thought, specifically with regard to the existentialist concept of incarnation and the ethical perspective of a life lived, by the self, in an intersubjective communion. This first part ends with Sorin Baiasu’s contribution (pp. 107-128), in which Sartre’s concept of freedom is established through dialogue and opposition with the Kantian perspective of freedom. Baiasu shows that the differences between the conceptions of these authors should not be understood, as is usually believed, as if the Sartrian view of freedom were an implausible radicalisation of the Kantian proposal.

The second part of this book deals with a perspective that is already present, albeit in the background, in the first part. It is about the importance, given by phenomenology, to intersubjectivity and the other. This importance leads us to the communicating vessels that phenomenology makes possible with social philosophy. The whole complexity here lies in identifying the influence that German idealism may have had on this phenomenological area of study. In some cases phenomenology will radicalise the perspective of German idealism in order to integrate the fundamental role of intersubjectivity, in other cases, the strategy will be to elaborate a critique of the tradition of German idealism against and its treatment of social problems, which will allow phenomenology to show itself as overcoming this tradition in response to these issues.

In his chapter (pp. 131-152), Jan Strassheim thus devotes himself to revealing the influence of the Kantian transcendental perspective on Alfred Schutz’s anthropology of transcendence, passing through Husserl’s critique of Kant’s anthropological theory. Strassheim shows that Schutz will insert intersubjectivity into his anthropological perspective inherited from Kant. First, the author shows in what sense Schutz’s anthropology has a phenomenological basis. Next, a difference is established between Kant’s and Schutz’s perspectives on transcendence. For the latter, transcendence will not be that which persists beyond all possible human experience, but rather transcendence “is a category for various ways in which human finitude appears within experience” (p. 137). Transcendence will also be understood on the basis of the concept of meaning and the concept of types, which will allow him to enlarge the Kantian categorical perspective. Intersubjectivity will be inserted here in order to understand the formation of the self.

In the article entitled “Moving Beyond Hegel: The Paradox of Immanent Freedom in Simone de Beauvoir’s Philosophy” (pp. 153-172), Shannon M. Mussett reveals the influence of Hegel’s Phenomenology of Spirit on Beauvoir’s conception of freedom as expressed in situations of oppression. Mussett argues that Beauvoir’s perspective is able to surpass the historical optimism of Hegelian dialectics by showing how immanent expressions of freedom can remain even in situations of oppression but in empty, abstract and ineffective behaviour. The paper begins by articulating the Hegelian notion of negative freedom by giving special attention to the dialectic of master and slave, which is for Beauvoir an instantiation of the optimism of the Hegelian system. Indeed, despite conditions of domination, the subject can, for Hegel, progress. Next, the author shows the ineffective forms of freedom according to Beauvoir, who not only radicalises the Hegelian perspective of freedom, but is capable of denouncing situations of oppression that only express themselves in empty social behaviour.

The last contribution in this part is that of Azzedine Haddour (pp. 173-199), who situates the dialogue between phenomenology and German idealism in the field of decolonial theory, also devotes special attention to the Hegelian dialectic of master and slave. However, this contribution focuses less on the notion of freedom implied in this dialectic than on the extra-philosophical conditions that make Hegel understand the issue of slavery in a particular way. Thus, the author of this chapter first analyses the position of the Hegelian dialectic vis-à-vis historical narratives that are read, by the system, in a teleological way, thus justifying slavery and infantilising people of colour. The Hegelian system is said to be founded on binary oppositions “premised on a Eurocentric and racialized view of the world” (p. 176). Haddour then draws a comparison between the Hegelian conception of slavery and Frantz Fanon’s decolonial theory. For Fanon, the fact that the world of the spirit is governed by rationality and that freedom is not one of its properties shows Hegel’s Eurocentrism. The Hegelian dialectic is dismantled then, in this paper, as counterintuitive.

If the second part of the book introduced social perspectives in the dialogue between phenomenology and German idealism, the third part of the book will deal with a central theme in order to clarify the deep constitution of the social: the theme of value, from an ethical and aesthetic perspective. David Batho’s contribution, entitled “Guidance for Mortals: Heidegger on Norms” (pp. 203-232), deals with the relationship between Heidegger and Hegel with regard to the normative constitution of the social. Batho argues with Robert Pippin, Steven Crowell and John McDowell, and defends that Heidegger’s concept of death as self-awareness of mortality is a necessary condition for grounding action in norms, which shows that Heidegger accounts for the self-legislation of agents as much as Hegel does.

Takashi Yoshikawa (pp. 233-255) focuses on Husserl’s Kaizo articles in order to point out the contribution of transcendental idealism to moral philosophy. Yoshikawa shows the influence of Kant and Fichte on the Husserlian idea of practical reason. In fact, Kaizo‘s ethical perspective shows, according to Yoshikawa, that as in German idealism, Husserl does not reduce reality to subjectivity. Rather, the transcendental idealism of Kant, Fichte and Husserl is not incompatible with empirical realism if we argue that the world exists independently of us. In fact, Kaizo‘s ethical perspective shows, according to Yoshikawa, that as in German idealism, Husserl does not reduce reality to subjectivity. Rather, the transcendental idealism of Kant, Fichte and Husserl is not incompatible with empirical realism if we argue that the world exists independently of us. In ethical terms, this translates into the defence of the virtue of modesty in the face of the incompleteness of our perception and the dependence of our action on the surrounding world.

María-Luz Pintos-Peñaranda discusses, in her chapter intitled “The Blindness of Kantian Idealism Regarding Non-Human Animals and Its Overcoming by Husserlian Phenomenology” (pp. 257-278), the issue of non-human animals. This subject, which would be indifferent to Kantian idealism, can be understood within Husserlian phenomenology. In this sense, the latter represents a real improvement of the idealist perspective. Pintos-Peñaranda first concentrates on Husserlian critique of Kant’s naturalistic logic, and then unveils the affinity of the concept of transcendental consciousness with non-human animals. Insofar as this concept is constituted on the basis of a pre-reflexive understanding that precedes it, animality occupies an important place in the unveiling of the origin of consciousness. Important implications of this are to be found in the phenomenological understanding of will, lived space and the capacity for spatialisation.

The contribution of Íngrid Vendrell Ferran, “Aesthetic Desinterestedness and the Critique of Sentimentalism” (pp. 301-322), explores the relationship between the Kantian tradition of aesthetics and the phenomenological perspectives of Moritz Geiger and José Ortega y Gasset. The absence of interest with which Kant characterises judgements of taste by emphasising the form of the work of art to the detriment of the content is here opposed to sentimentalism as a defect in aesthetic appreciation. Geiger and Ortega y Gasset are equally opposed to sentimentalism in aesthetics following Kant, but the former emphasises aesthetic value while the latter emphasises the formalism of aesthetics.

The fourth part of this book touches on a fundamental theme for both phenomenology and German idealism. This is the one concerning temporality and historicity, which implies going through the concept of memory. Some of the authors in this part argue for a convergence of perspectives between phenomenology and German idealism, while others oppose them, and still others dispute the erroneous readings of German idealism by representants of phenomenology.

Thus, Jason M. Wirth’s contribution (pp. 325-341) brings Schelling and Rosenzweig into dialogue with regard to the time of redemption. On the basis of a cross-reading between the two philosophers, Wirth argues that idealism is redeemed when truth is located between philosophy and theology, between the side of the intellect and that of revelation. In this sense, what is eternal is realised within the concrete completeness of time. Markus Gabriel, in his chapter entitled “Heidegger on Hegel on Time” (pp. 343-359), first reconstructs the reading of Hegel in Being and Time, and then answers it on the basis of a reading of the Hegelian texts. Finally, he criticises Heidegger’s existentialist perspective on temporality. Gabriel argues that Heidegger does not attend to the methodological architecture of the Hegelian philosophical system because he assumes that this system is a historicised form of ontotheology, which is totally inaccurate. In fact, the Heideggerian reflection on time in general fails with respect to the relation between nature and history.

In her paper, Elisa Magrì (pp. 361-383) explores the relationship between Hegel and Merleau-Ponty with regard to sedimentation, memory and the self. Firstly, sedimentation is understood, in Merleau-Ponty’s thinking, as inseparable from the institution as a process of donation of meaning. Magrì interprets this understanding as a revised version of Hegelianism. Hegel’s concept of absolute knowledge is comprehended here as a process of sedimentation that implies a process of institution. The Hegelian concept of absolute knowledge is finally related to a kind of ethical memory that reactivates potential new beginnings in history and society as a form of critique. This contribution closes by pointing out the ethical value of memory for contemporary debate. On the basis of Merleau-Ponty’s and Hegel’s thought, we can understand memory, according to Magrì, as the constant institution of the self, and not as its neutralisation. Memory thus helps to avoid repeating mistakes and to germinate a new dimension for collective reflection and action.

Zachary Davis focuses his contribution (pp. 385-403) to Max Scheler’s idea of history and shows how it has been influenced by German idealism. Davis explores the different periods of Scheler’s thought. The first period, strongly phenomenological, is marked by discussions with the Munich circle and their views on history. In this period, Scheler shares with Hegel the belief that there is an idea in history which develops in the life of culture. However, Scheler criticises the Hegelian perspective that would see history solely as the realisation of the spirit and historical progress as the realisation of absolute knowledge. Historical progress is seen by Scheler as the socialisation of material conditions and the individualisation of spiritual values. Scheler opposes Hegel’s impersonal view to a personalistic view of the spirit. In the last, anthropologically oriented period of his philosophy, Scheler refers to Schelling’s thought. Contrary to Schelling’s internalist view, Scheler argues that there are external material conditions for the realisation of history.

The fifth part of this book unveils the ontological and epistemological discussions that phenomenology entertains with German idealism. The latter appears, in these phenomenological perspectives, sometimes as a presence, sometimes as something to be overcome, sometimes as a persistence. The contributions gathered here focus exclusively on the non-Husserlian approaches of phenomenology. Thus, Mette Lebech, in her article entitled “The Presence of Kant in Stein” (pp. 407-428), focuses on the questions of idealism and faith in Edith Stein and how these relate to Kant’s influence on her phenomenological approach. Lebech articulates Stein’s engagement with Kant through Kant’s influence on Reinach and Husserl. This allows him to elaborate an idea of phenomenology as an extension of the Kantian understanding of the a priori and to oppose Husserl whom he labels a metaphysical idealist. Finally, Lebech argues that Kant signifies, in Stein, the beginning of a philosophical thought that can be articulated with faith. For his part, M. Jorge de Carvalho (pp. 429-455) makes us reflect on Heidegger’s interpretation of Fichte’s three principles. These principles will be understood here in an existentialist key with regard to the question of finitude. For Heidegger, Fichte’s preoccupation with constructing a system of knowledge prevents him from exploring the temporal and existential problems of Dasein analysis.

Jon Stewart (pp. 457-480) explores the relationship between the phenomenological method in Hegel and the later movement of phenomenology. Although it is known that Hegel and Husserl do not share the same concept of phenomenology, according to Stewart, some of the post-Husserlian phenomenologists know Hegel well. The question this article attempts to answer is therefore whether they attempt to approach the Hegelian sense of phenomenology. The article begins by showing the meaning of phenomenology for Hegel and then sets out the Husserlian critique of Hegel, before pointing out Hegel’s influence on French phenomenology, specifically on Sartre and Merleau-Ponty. Stewart concludes that while there are differences between the latter’s and Hegel’s sense of phenomenology, we find in the phenomenology of Sartre and Merleau-Ponty a clear Hegelian influence because of the importance they gave to Hegelian thinking, unlike Husserl.

The paper by Stephen H. Watson, entitled “On the Mutations of the Concept: Phenomenology, Conceptual Change, and the Persistence of Hegel in Merleau-Ponty’s Thought” (pp. 481-507) somewhat extends the reflections of the previous chapter. Taking as evidence the Hegelian influence on Hegel’s thought, Watson identifies the ideas of Hegel, both systematic and metaphysical, that Merleau-Ponty draws on to elaborate his theory of behaviour and perception in his early thought. We then participate in the resolution of some paradoxes that, in the period of Merleau-Ponty’s expression of thought, appear regarding the relation between system and subjectivity. Finally, Watson shows the influence of Schelling and Hegel on Merleau-Ponty’s last period in which a new ontology is formulated.

Interpretation being one of the fundamental themes of the phenomenological movement, which has made possible the formation of a hermeneutic variant of phenomenology, a final part of this book seeks to identify the influences of German idealism for the proposals of three exponents of this variant: Heidegger, Gadamer and Ricoeur. However, this part of the book escapes the question of whether there would be a real continuity between the phenomenological project and the hermeneutic project, and whether hermeneutics would not have its own origin in the philological sciences and in the interpretation of sacred texts, disciplines that precede the birth of phenomenology. In any case, the question at issue here is whether the hermeneutics that takes place within the phenomenological movement has been influenced by German idealism.

Frank Schalow thus focuses, in his chapter (pp. 511-528), on the importance of Kantian transcendental philosophy for Heidegger’s hermeneutics, which would be a radicalisation of certain Kantian theses, specifically with regard to the power of the imagination. The chapter begins by showing the relationship between the cognitive sense of imagination in Kant and its linguistic and temporal sense. Schalow then shows how Heidegger deconstructs the rationalist tradition of German idealism with his reinterpretation of the Kantian imagination and extends his critical view of Kantian metaphysics to the realm of ethics. Besides, Heidegger’s reading of Kant allows him to distinguish himself from German idealism, in terms of the dialectical method, the metaphysical implications and the place of language in all this. It is here that Heidegger’s hermeneutics finds its specificity, in terms of a deconstructive imagination in which language plays an essential role, as opposed to the systematising rationality of German idealism. Particular attention is given here to Kant’s influence on Heidegger’s aesthetic theory, which also allows him to return to a particular exponent of German idealism, Hörderlin, in order to rediscover the confluence between poetry and truth.

Theodore George’s paper entitled “Gadamer, German Idealism, and the Hermeneutic Turn in Phenomenology” (pp. 529-545) concentrates on the fundamental hermeneutic concepts of facticity, history and language. In contrast to Husserl and Heidegger, Gadamer considers that in Hegel and German idealism we find philosophical perspectives that can be integrated into his hermeneutics, although in order to do so we would have to break with a neo-Kantian reading of this tradition. The author first locates the place of the hermeneutic turn of phenomenology in Gadamer’s thought. Like many students of his generation, Gadamer, according to George, found in both existentialism and phenomenology an alternative way to escape Neo-Kantianism. Later, he was strongly influenced by “Heidegger’s hermeneutical intervention against Husserl’s phenomenology” (p. 534). But if Gadamerian hermeneutics certainly begins with a critique of the inherited forms of consciousness that we receive from German idealism and the Romantic tradition as forms of alienation, we find in it, paradoxically, a positive reception of Hegel. Hegel allows Gadamer to articulate the role of history and language in the hermeneutics of facticity.

Robert Piercey’s contribution shows that Ricoeur’s relation to Hegel is paradoxical since we find different versions of Hegel in Ricoeurian thought. Hegel appears here in methodological, ontological and metaphilosophical form. In fact, the author argues that renouncing Hegel, for Ricoeur, does not mean renouncing dialectical thought altogether or renouncing all Hegelian ontological tendencies. On the contrary, it is a matter of avoiding only unrealistic promises that dialectical thought believes it can keep. It is therefore a critique of a particular metaphilosophy. Although Ricoeur criticises Hegelianism, Hegel is an important philosophical source for his hermeneutical thinking.

The book concludes with a reflection by Cynthia D. Coe (pp. 547-575) that attempts to situate the different historical contexts of German idealism, on the one hand, and phenomenology, on the other, showing that both traditions still have much to offer for the current historical context that is ours. From enviromental ethics to the relationship between life and technology, the sense of humanity and its relationship to the world that we forge through the study of these traditions still has much to offer. We can only invite those interested in these traditions, but also those interested in the various philosophical disciplines, to immerse themselves in the timeless and fruitful dialogue that this book establishes, by many voices, between phenomenology and German idealism.

References

Husserl, Edmund. (1970). Crisis of European Sciences and Transcendental Phenomenology: An Introduction to Phenomenological Philosophy, David Carr (trans.), Evanston: Northwestern University Press.

Lazzari, Riccardo. (2009). Eugen Fink e le interpretazioni fenomenologiche di Kant, Milan: Franco Angeli.

Matherne, Samantha (2016). “Kantian Themes in Merleau-Ponty’s Theory of Perception”, Archiv für Geschichte der Philosophie 98 (2):193-230.

Slama, Paul. (2021). Phénoménologie transcendantale. Figures du transcendantal de Kant à Heidegger, Cham: Springer, coll. “Phaenomenologica”, vol. 232.

Schnell, Alexander. (2009). Réflexion et spéculation. L’idéalisme transcendantal chez Fichte et Schelling, Grenoble: J. Millon, coll. “Krisis”.

Steinbock, Anthony. (2017). Limit-Phenomena and Phenomenology in Husserl, Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield International Ltd.

The Political Logic of Experience: Expression in Phenomenology

The Political Logic of Experience: Expression in Phenomenology

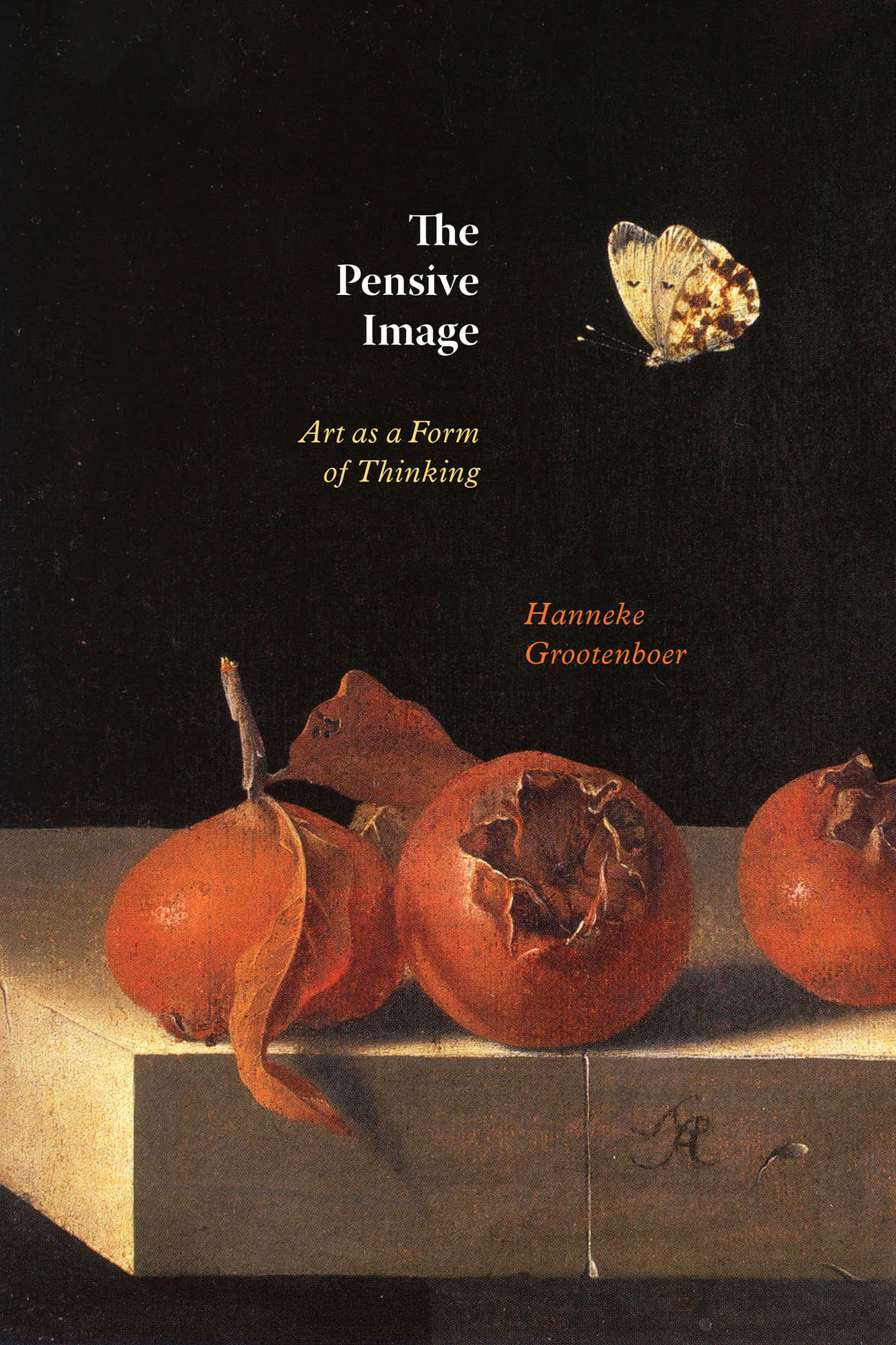

The Pensive Image: Art as a Form of Thinking

The Pensive Image: Art as a Form of Thinking

Reviewed by: Kayla Dold (Master’s of Arts student in the Department of Political Science, Carleton University, Ottawa, Ontario)

Why is there being instead of nothing? Hanneke Grootenboer’s The Pensive Image: Art as a Form of Thinking takes this Heideggerian question as it’s starting point. Like Martin Heidegger, Grootenboer’s task is to reflect on what constitutes philosophical thinking about being. In a discipline like philosophy, with its wide array of methodological approaches, traditions, and applications, it is easy to lose sight of simple yet profound questions like Heidegger’s. In this sea of approaches, Grootenboer’s book provides an accessible, clear, and innovating means of thinking about being by revealing a new philosophical subject: artworks.

In a succinct five chapters, Grootenboer describes a means of doing philosophy with pensive images. This is an ambitious task; however, for all its brevity (its body is approximately 170 pages), The Pensive Image remains philosophically vigorous and firmly rooted in the philosophical traditions that precede it, including German idealism, romanticism, phenomenology, post-structuralism, and of course, modern and contemporary art history. It is a blend of modern Western philosophy and art history; while Grootenboer discusses some contemporary artworks (like Richard Estes’ photorealism in chapter five), their focus is on seventeenth century Dutch artworks and modern continental philosophy. Its blend of continental philosophy and modern art produces a hybrid means of philosophizing and expands our conception of what is philosophically relevant to include modern artworks.

Despite their blend of philosophy and art, Grootenboer’s attention to detail and clear prose is consistent throughout, making The Pensive Image a valuable resource for art historians, philosophers, students, and the general public. Its clarity and wide range of commentary makes The Pensive Image interesting and accessible for a general audience, while its theoretical contributions to philosophical methods makes it valuable to the undergraduate and highly trained researcher alike.

Grootenboer’s The Pensive Image describes a novel philosophical subject—the pensive image—and prepare it for application in art history (15). Grootenboer justifies this task by arguing that philosophy (insofar as it is interested in reflection, being, essence, and thinking) needs artworks to articulate complex and layered clusters of concepts that are difficult, or impossible, to articulate with words (5). Visual arguments articulate clusters of concepts that are related yet cannot be systematically explained using cause and effect, logic puzzles, or thought experiments. Therefore, visual arguments add invaluable tools to our philosophical tool belts; however, this methodological implication is not the book’s sole source of value.

The Pensive Image does not only describe a new philosophical subject and means of thinking about being. Grootenboer’s meticulous invocation of the Western philosophical tradition, ranging from Descartes to Deleuze, offers us clear and descriptive secondary literature on great philosophical minds. The Pensive Image provides excellent commentary on those whom Grootenboer builds their theory (including Descartes, Diderot, Kant, Locke, Hegel, Herder, Goethe, Heidegger, Barthes, Lessing, Rancière, and Deleuze, amongst others). For example, the description of Heidegger’s conception of uncanniness [unheimlich] from Being and Time in chapter three is as clear and succinct as the description of dewdrops on flower petals in chapter four. Its balance between commentary and description makes The Pensive Image an indispensable handbook to anyone interested in the history of the philosophy of mind, the philosophy of art, and their intersection in the Western continental tradition.

While The Pensive Image provides clear and detailed commentary on other thinkers, it is primarily methodological. Despite its engagement with artwork, it is not hermeneutical. Instead, it follows Edmund Husserl’s original phenomenological directive: to pay close attention to things themselves. Grootenboer’s approach depends on describing artworks as autonomous philosophical subjects. Through a careful consideration of images and their effects on their viewers, Grootenboer describes a relationship between artwork and viewer that does not depend on interpretation, cracking a code, or deciphering a message. Instead, Grootenboer pays close attention to the visuals presented—a open door, a vast black background, the translucent shine of dew on a flower petal—and how these direct our thoughts. Throughout The Pensive Image, Grootenboer acknowledges that these effects may or may not have been the intension of the artist (5, 59, 60, 97, 99, 122, 146). Either way, intentionality (or lack thereof) does not change the artwork’s effect, its capacity to mediate our process of reflection, or to direct our thoughts (10-11). Whether or not Grootenboer’s description and conclusions are possible without an interpretive element is the topic for another book; regardless, Grootenboer describes interactions with artworks readers have likely experienced themselves. It is their description of our shared experience of artworks that makes Grootenboer’s conception of the pensive image and its application so compelling.

What exactly is a pensive image, and what are its effects? Grootenboer’s first section, “Defining the Pensive Image,” describes this philosophical subject and justifies its relevance to modern continental philosophy and art history. Grootenboer sets up their description with an account of the relationship between philosophical thinking and artworks over time. They situate the pensive image in two related traditions: the phenomenology and the relationship between modern artworks and contemplation. Thus, Grootenboer does more than simply revive Heidegger’s question of why there is being. They also situate the pensive image in a tradition of phenomenological approaches to art taken by Heidegger and Maurice Merleau-Ponty (1-5).

Grootenboer then surveys the historical relationship between modern artworks and philosophy. Grootenboer describes their thesis as a secular extension of the medieval tradition of contemplation, which uses images as mnemonic devices to transcend the secular domain (3). Grootenboer also notes how many modern philosophical ideas were explained using visual representation, though the intimate relation between art and philosophy generally declines after the seventeenth century (4). Thus, Grootenboer’s thesis revives and expands upon a previous philosophical tradition and is legitimized by its relation to phenomenological approaches to artworks.

The Pensive Image argues for the relevance of artworks to philosophy on multiple levels. Broadly speaking, it argues that artworks are a form of thinking. Artworks offer viewers entrance into a mode of thinking we would not enter on our own (1). This does not mean the artwork offers a particular narrative or meaning but that it inspires a new train of thought (22). Grootenboer writes that pensive images are “those that confront us in such a way that our wondering about the work of art—its subject of meaning—is transformed into our thinking according to it” (6). Rather than offering a narrative, a pensive image offers us the opportunity to think by guiding our thoughts in ways we might not have gone without its inspiration. This presupposes artworks can be effective: they do something to us. Therefore, pensive images are not meant to be interpreted but experienced.

Specifically, The Pensive Image argues that modern Dutch painting includes pensive images that guide our thoughts and reflections on being. (Though its focus is modern Dutch art, the book includes commentary on film and photography that helps us understand how different forms of art are concerned with different questions.) The first chapter, “Theorizing Stillness,” is devoted to describing the particulars of the pensive image as it applies to Dutch painting. The pensive image has two chief characteristics: firstly, while its meaning is indeterminant, a pensive image redirects our thoughts to contemplate being in new ways. It initiates a line of thinking we can follow indefinitely (9). It is not there to draw conclusions but to serve as an opening that allows a multiplicity of ideas to exist at the same time. Secondly, a pensive image visualizes a snapshot in time. This frozen moment, the anticipation of something more that is not visually articulated, is what directs our thoughts (24). A pensive image is therefore characterized by a movement paradox. Its stillness arrests us and from this arrest comes a flow of thought; pensive images generate “a passive, uneasy, and indeterminant state of openness that allows for the unthought to surface” (26). A pensive image is open, tense, and suggests the possibility of movement (37). It stops our thoughts to redirect them in a new direction undetermined by specific signs or signifiers, meanings or narratives.

If the pensive image does not signify meaning nor tell stories, what does it contain, or, in other words, what is its essence? Chapter two, “Tracing the Denkbild,” answers this question. Instead of a specific signification, the pensive image is the embodiment of thought. This chapter describes different means of understanding an image as embodied thought over time. Through an analysis of stillness, it argues that the pensiveness of a pensive image can be understood as a moment of anticipation (47). Here, stillness is characterized by the theoretical potential for movement, rather than a lack of movement. Thus, tension, anticipation, and potential define a pensive image; it is open, uneasy, and ambiguous. Its openness and ambiguity make the pensive image a valuable philosophical subject worthy of our engagement.

While the idea that painting can be more than images on a canvas is not new, Grootenboer invites us to see painting as a partner in philosophizing that guides us where ‘it’ wants us to go (11). This metaphor of movement, guidance, and journey is central to Grootenboer’s pensive image and recurs through the book. For example, landscape paintings are “maps” that help viewers shape their interior selves, “entrances” into the pictorial realm (2, 1). They invite us to “dwell” within them, they reach out and touch us, set things in motion, and vibrate with potential (5, 26, 43). We are invited to get lost in the image, to rest in it, or to bord it like a vehicle (77, 78). Like Lucy, Edmond, and Eustice in C.S. Lewis’s The Voyage of the Dawn Treader, who are literally pulled into a painting of an ocean, allowing the pensive image to direct our thoughts is like being carried away by a wave (58). The tension between stillness and motion, journey and rest are fundamental to the pensive image.

Chapter three expands upon these relationships to think through what Grootenboer pithily calls philosophy’s housing problem. In this chapter, Grootenboer’s philosophical subjects include paintings of bourgeois Dutch homes and a dollhouse. These artworks provide a place for our thoughts to dwell, or, in Grootenboer’s words, “a home for the philosophical self,” by offering the opportunity to reflect on the permeable membranes between publicity and retreat, inside and outside (79). This chapter describes how artworks serve as metaphorical spaces where we can house our thoughts and subjectivities, thereby solving philosophy’s housing problem.

Drawing theoretical support from René Descartes’ construction metaphor and Heidegger’s conception of dwelling, Grootenboer demonstrates how Emanuel De Witte’s Interior with Woman at a Virginal (c. 1660–1667) and Petronella Oortman’s dollhouse (1686– 1710) host our thoughts. Descartes compares self-reflection to construction: in order to achieve self-understanding, we must clear away old foundations and build anew (81). Descartes himself formulated this approach while traveling. In his home-away-from-home, Descartes constructs himself a metaphorical home to house his thoughts and reflections (82). To philosophize is therefore conceived of as being on a mental journey while physically at rest. This implies that the philosopher’s home is not an actual resting place but their journey: the act of philosophizing itself.

Grootenboer builds on this tension between journey and rest by invoking Heidegger’s conception of dwelling. Heidegger argues that constructing something implies we already dwell there (85-86). To dwell implies a movement towards materiality. For Heidegger, dwelling is not a static condition but a constant movement towards something that cannot be achieved (to achieve it would no longer be to dwell). It is to be drawn towards something without ever arriving, a constant becoming (87). De Witte’s interior painting, as a pensive image, helps us understand this situation. It allows our thought to dwell within it. Our eyes and subsequent thoughts are drawn through doorways to the vanishing point beyond, a point we will never actually behold.

While we cannot inhabit De Witte’s painting, Oortman’s dollhouse appears inhabitable. Yet, because the dollhouse replicates Oortman’s home on a miniature scale, it is ultimately uninhabitable, what Grootenboer calls “a borrowed home” (105). That being so, the dollhouse contains elements, like a collection of seashells, that provide an opportunity to think through the dialectics of inside and outside and journey and rest. For example, what was once the travelling home of a sea creature is now an empty shell. The dollhouse allows us the opportunity to think through the uncanny nature of uninhabitable spaces that appear inhabitable. What these artworks offer us is not the ability to determine what is inside and outside, on journey or at rest, but to recognize that as philosophical subjects, we are wanderers (109). It is the pensive image, which offers a temporary place to dwell, that saves us from getting lost.

In chapter four, “The Profundity of Still Life,” Grootenboer analyzes pensive images that guide us through the relationship between finitude and infinity. For example, Adriaene Coorte’s Three Medlars and a Butterfly (1696-1705) mediates our understanding of the relationship between the infinitively large and the finitely small by visualizing a small butterfly approaching three fruits against a black background (119). The painting serves as a plot point between two extremes: the expansive background and the small butterfly. We can use this point as a reference when thinking through the implications of each extreme. This pensive image provides perspective; the butterfly and fruit in the foreground impose a sense of proportion, direction, and space onto a painting that would otherwise stretch into infinity. Grootenboer’s analysis suggests that as situated subjects, we are unable to think through the implications of limitlessness or infinity without a mental anchor or reference point. We can only understand infinity through its comparison with the finite, which Three Medlars and a Butterfly provides. By describing Three Medlars and a Butterfly in detail, Grootenboer demonstrates its philosophical relevance. By mediating our conceptualization of infinity, it embodies a form of thinking and self-reflection (133).

Grootenboer moves past self-reflection in the final chapter, “Painting as Space for Thought,” to invoke G. W. F. Hegel’s conception of self-consciousness. Hegel writes that painting’s function is not to reflect the world, but to provide some permanence for contemplation (135). For Grootenboer and Hegel, what inspires contemplation is shine. Painting is unique amongst artistic mediums in its capacity to represent light and to, therefore, shine (136-138). In this chapter, Grootenboer contrasts Hegel’s conception of self-consciousness with self-reflection, arguing that photorealism is a self-conscious genre whose self-consciousness helps us better understand Hegel’s concept. Grootenboer argues this point via an analysis of shine in Richard Estes’s photorealism.

Where does a reflection lie? In the object that reflects, or the subject that is reflected? Richard Estes’s Central Savings (1975) mimics a photograph of a storefront, in which the objects on the street are reflected and layered on top of each other so that we are unsure what is inside or outside the store. Estes’s painting serves as a means to reflect on reflection, visualizing both the reflected subjects and objects in which they are reflected. The painting is therefore both itself and its negation or mirror image, providing us an opportunity to think through the dialectic of self and other. The painting, whose self-consciousness comes from its ability to facilitate a synthesis of reflected and reflection, helps us think past this dialectic and synthesize the two (142-143).

Estes’ painting does not separate inside from outside nor opacity from transparency. Instead, it allows us to see how what is reflected always meets itself in its reflection, preventing an endless cycle of reflection in a synthesis of reflection and reflected (156). Central Savings, like Hegel’s conception of self-consciousness, is bold enough to think through and overcome oppositions (159). Grootenboer’s analysis of Central Savings reveals that the philosophical tradition of reflecting on reflection is not exclusive to written philosophy. It is enacted by pensive images as well.

Grootenboer concludes The Pensive Image with commentary on the relationship between philosophy and wonder. Grootenboer reminds us that according to Plato, Socrates believed wonder was the beginning of philosophy (167). Do artworks offer a similar starting point? For Heidegger, wonder is a basic element of ordinary life (168). According to Grootenboer, the association between wonder, philosophy, and ordinary life is what makes seventeenth century Dutch artworks such fruitful contributors to philosophical investigations of being. Their focus on the ordinary and their reward of slow looking leads us to new discoveries. Ultimately, the pensive image is a valuable philosophical subject because it provides the opportunity to philosophize from, and about, ordinary experience. They stop us in our tracks and suggest a new courses for our philosophical journeys. In contrast to trompe l’oeil, panorama, of other kinds of illusionism that overwhelm us by enchantment and delight to lift us out of our ordinary experience, pensive images slowly overtake us. They do not to lift from the ordinary but to push us deeper into it, guiding us home (169). The Pensive Image thus concludes with all the optimism a new philosophical approach deserves, the hope for new discoveries that bring us home to ourselves.

The Pensive Image has the potential for broad application. Its description of the pensive image, its commentary on painting, film, and material culture, and its overlapping imagery with literary analysis implies the possibility of using the pensive image to understand the philosophical importance of other cultural products. The pensive image, applied metaphorically to literary imagery, might reveal an intimate relationship between image, text, and mind, in which the text’s imagery compels us to follow its logic. This, combined with its phenomenological approach, provides a framework we can apply to the existential literature of Simone de Beauvoir, Jean Paul Sartre, Albert Camus, and others. For example, Beauvoir’s imagery of barren wastelands in her 1946 novel All Men Are Mortal guides us through a similar meditation on finitude and infinity as Grootenboer describes in chapter four, implying an opportunity for comparison and new perspectives. Grootenboer’s The Pensive Image describes an approach potentially more far reaching than its introduction’s humble proposal, which could potentially be applied to imagery in literature, film, performance art, and even music.

While it is sometimes difficult to discern whether Grootenboer argues in favour of artworks as aids to understanding philosophical ideas articulated elsewhere (as is the case for Heidegger’s dwelling or Hegel’s self-consciousness) or as containing autonomous philosophical arguments themselves (as is the case for Three Medlars and a Butterfly), their oscillation between the two demonstrates that for artworks to be taken seriously as philosophical subjects, we do not have to decide between one and the other. As a philosophical subject, a pensive image can clarify an idea articulated elsewhere without depending on others’ ideas to articulate its own arguments. Its status as independent philosophical subject does not preclude its ability to aid our understanding of others.

Some aesthetic purists might balk at the idea of using artworks this way. They could argue that art is meant to be enjoyed, valued for its own sake, rather than used for philosophical ends. Grootenboer successfully counters such arguments by describing how the pensive images’ effects are part of its being. We do not use a pensive image for our own purposes. Instead, we let it guide our thoughts according to its own logic. Grootenboer thus avoids accusations of the ‘use and abuse’ of artworks for philosophical ends by focusing on the artworks themselves, their effects, and their autonomous properties. Rather than using a pensive image to achieve our own goals, we enter into a relationship with it. We following it where it needs to go without the added baggage of hypotheses, interpretive frameworks, or ulterior motives. Engagement with pensive images allows us to engage in a philosophy of free play, curiously, and wonder, rather than one of hermeneutic or analytical investigation. It is an appreciation of the things themselves without contorting them by imposing artificial frameworks and hypothesis.

In addition to its methodological implications, The Pensive Image challenges the artificial distinctions between art and philosophy, perceiving and thinking, reason and emotion. It models how to challenge disciplinary boundaries, which can get in the way of innovative thinking. Grootenboer conceptualizes the pensive image as a “predisciplinary blueprint” because it directs the thinker on a journey that knows no disciplinary bounds, be they philosophical, historical, literary, or artistic (71). Its most valuable contribution to philosophy is its emphasis on philosophy as a conscious reflection unbound by discipline, subject, or object.

In chapter three, Grootenboer writes that their main concern is not what thought is but how artworks help house it. The Pensive Image might not focus on defining thought but implies a simple yet profound definition of philosophy: a free flow of reflection, contemplation, and investigation mediated by permeable boundaries, boundaries that allow for movement so that dwelling and journeying merge. The Pensive Image provides us with a vision of philosophy and art in a mutually constituting relationship, a roadmap to theoretical places yet unexplored, and thereby a philosophical home.

La conscience interne de la langue: Essai phénoménologique

La conscience interne de la langue: Essai phénoménologique